Promises

Some Kept, Many Unfulfilled

Freedoms first exercised by African Americans in the Sea Islands would soon find expression in new amendments to the Constitution. But many of the promises of Reconstruction went unfulfilled.

While civil rights amendments were enacted on the national stage, efforts to stifle the liberties of African Americans in the Sea Islands rose. In November of 1877, the Beaufort Black militia was forced to disband and reorganize under new, state-mandated leadership.

Reconstruction on the National Stage

The Rehearsal in the Sea Islands previewed many of the achievements and challenges that the nation would face during Reconstruction across the South. The civil rights African Americans exercised for the first time in the Sea Islands would eventually find expression in the most significant amendments to the Constitution ever made. But the refusal by white Southerners to abide by the new Constitution, and the nation’s lack of commitment to enforcing the amendments, would leave many of the promises of freedom and equality unfulfilled.

Appomattox Courthouse, Va. April. United States Virginia, 1865. Photograph. Library of Congress

By the Summer of 1865, the U.S. military victory brought hope for freedom, equality, and opportunity to freedpeople everywhere. Yet, Black people still faced prejudice, hostility, and violence. In much of the South, plantation owners still dominated state and local politics. These planters fought to preserve as much of the old slavery system as possible. They encouraged white Southerners of all classes to see Black people as hostile enemies, unworthy of freedom or equal rights.

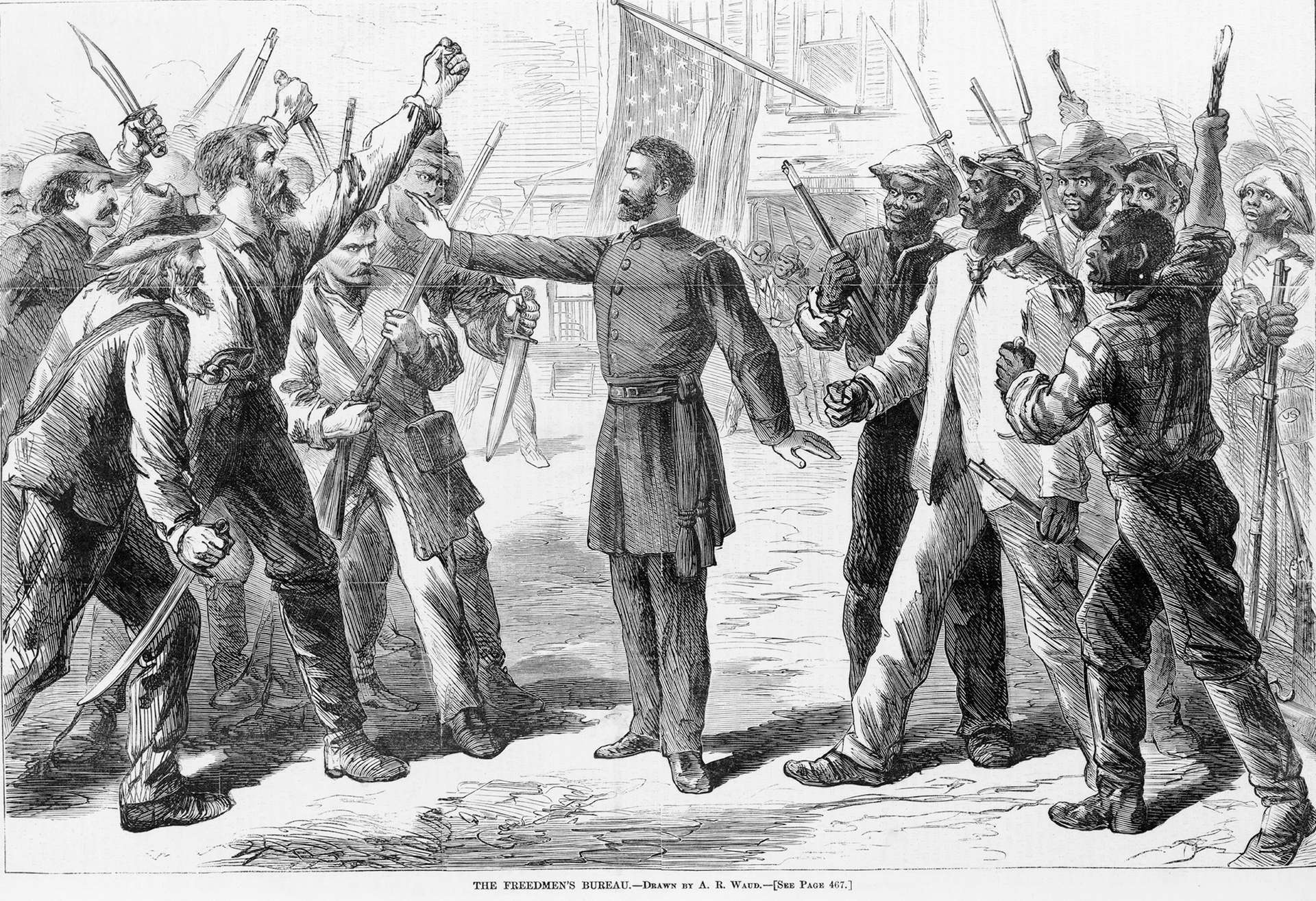

Waud, Alfred R., Artist. The Freedmen's Bureau / Drawn by A.R. Waud, 1868. Photograph. Library of Congress

On March 3, 1865, U.S. Congress established the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, more commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau. Staffed mostly by U.S. soldiers, the Freedmen’s Bureau was tasked with managing the transition from a slave labor system to a free labor system. Bureau agents intervened in labor contract negotiations and established courts where Black people were to receive justice. They built schools and performed marriages between freedpeople. They reunited families forcibly separated during years of slavery and war. The Bureau was responsible for redistributing parcels of confiscated land to freedpeople.

Brady, Mathew B., Approximately, photographer. [Photographed between 1860 and 1875] Photograph. Library of Congress

After Abraham Lincoln’s death by assassination on April 15, 1865, Vice President Andrew Johnson assumed the office of the Presidency. He began pardoning former Confederate plantation owners and returning their lands to them. This often meant taking back land from a formerly enslaved family who now occupied it. Many freedpeople were forced to leave their land or begin working for white people, instead of farming for themselves. Still, many managed to hold on, particularly in the Sea Islands. The Republican-led South Carolina government established a land commission in 1869 to buy plots of land and sell them to freedpeople at affordable prices. By the end of 1890, 14,000 African American families in South Carolina had settled on these lands.

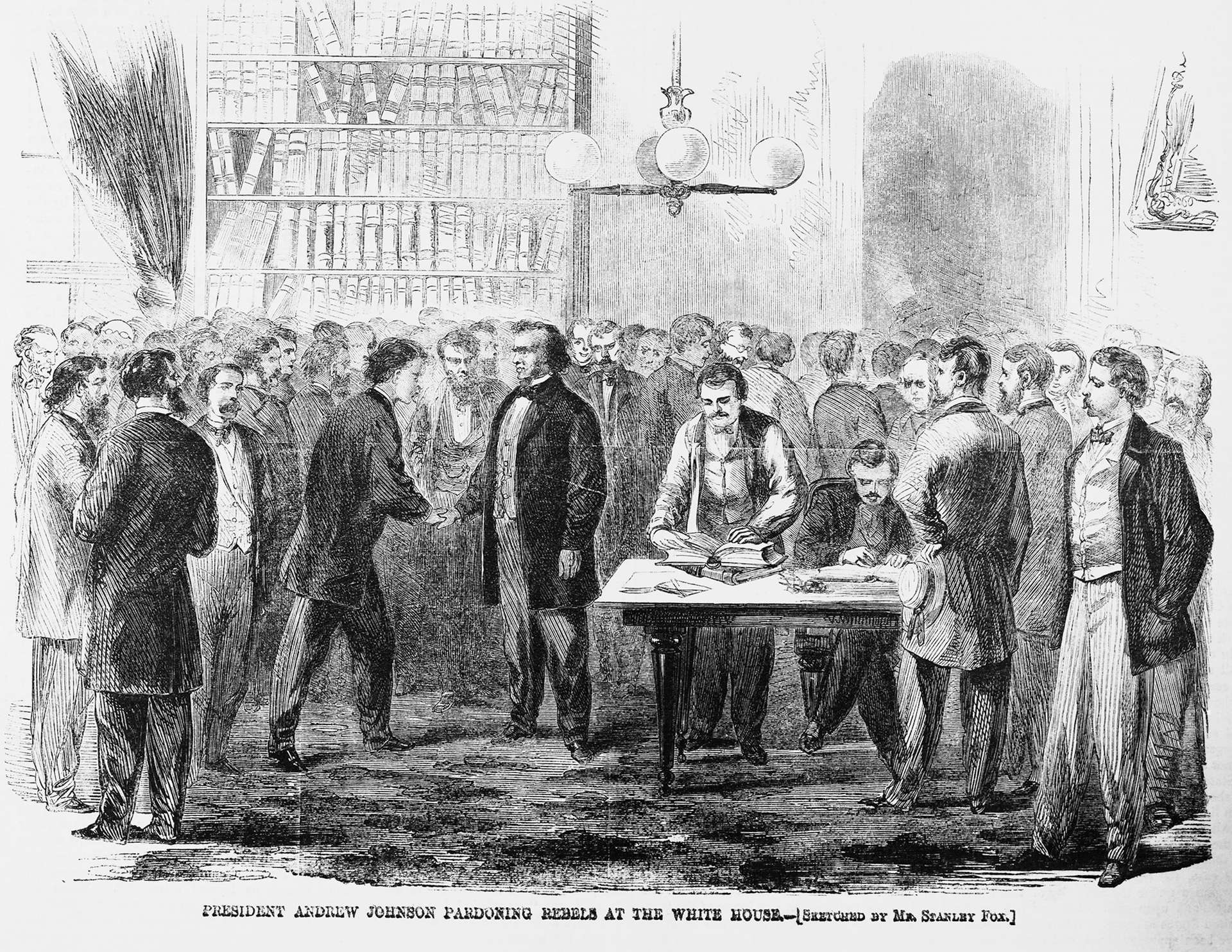

Fox, Stanley, Artist. President Andrew Johnson pardoning Rebels at the White House / sketched by Mr. Stanley Fox. United States Tennessee, 1865. Photograph. Library of Congress

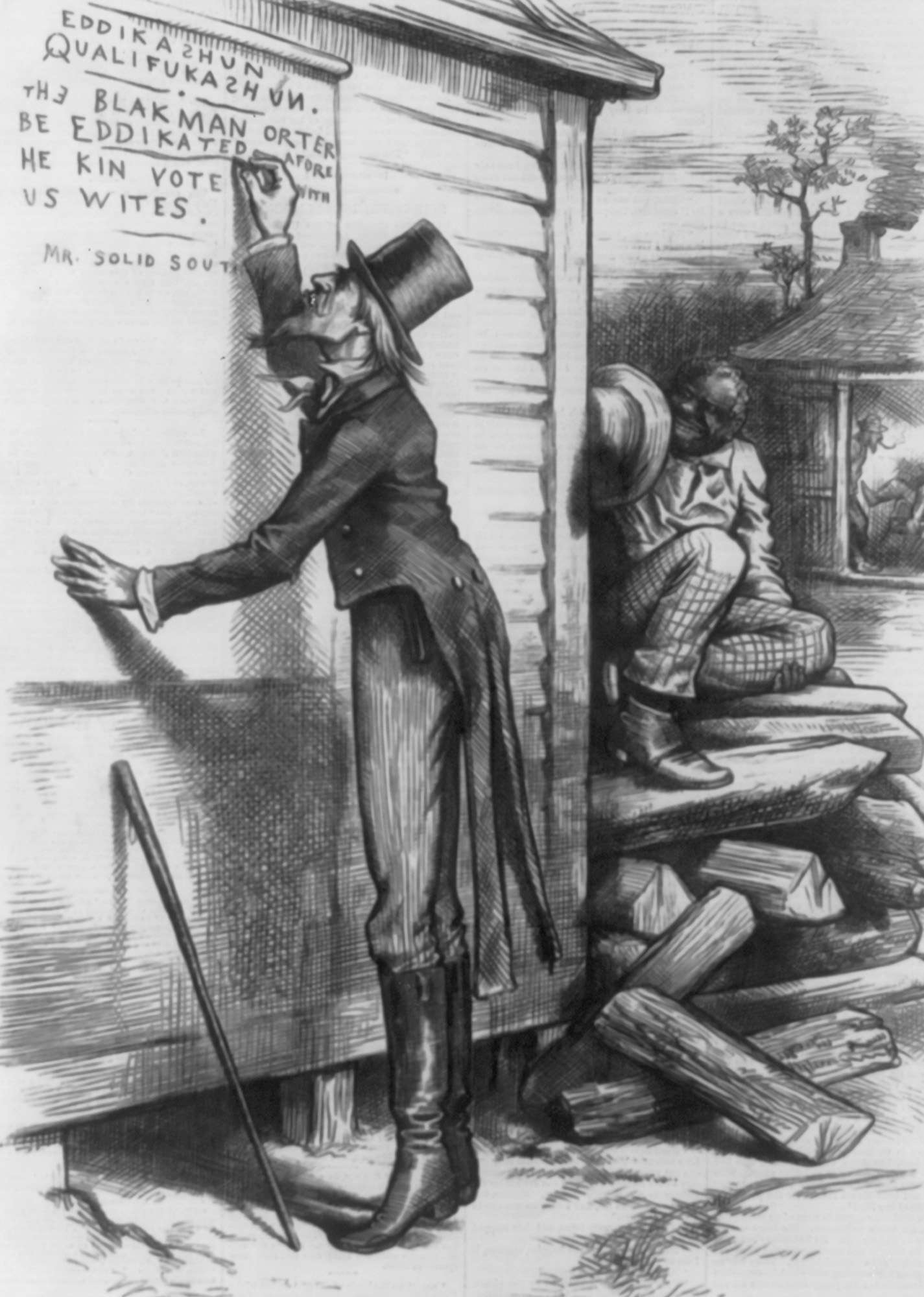

Through President Johnson’s Reconstruction program, white Southerners gained control of Southern state legislatures, while continuing to prohibit Black men from voting. These lawmakers passed laws to subjugate freedpeople and restrict their ability to exercise their rights. Laws known as Black Codes made it a crime for a Black person to fail to sign a labor contract with a white employer. In Mississippi, the Black codes prevented Black people from owning land. All over the South, the codes made it illegal for them to serve on a jury or testify in court, just as it had been under slavery. No Southern state allowed Black men to vote in the immediate aftermath of the war.

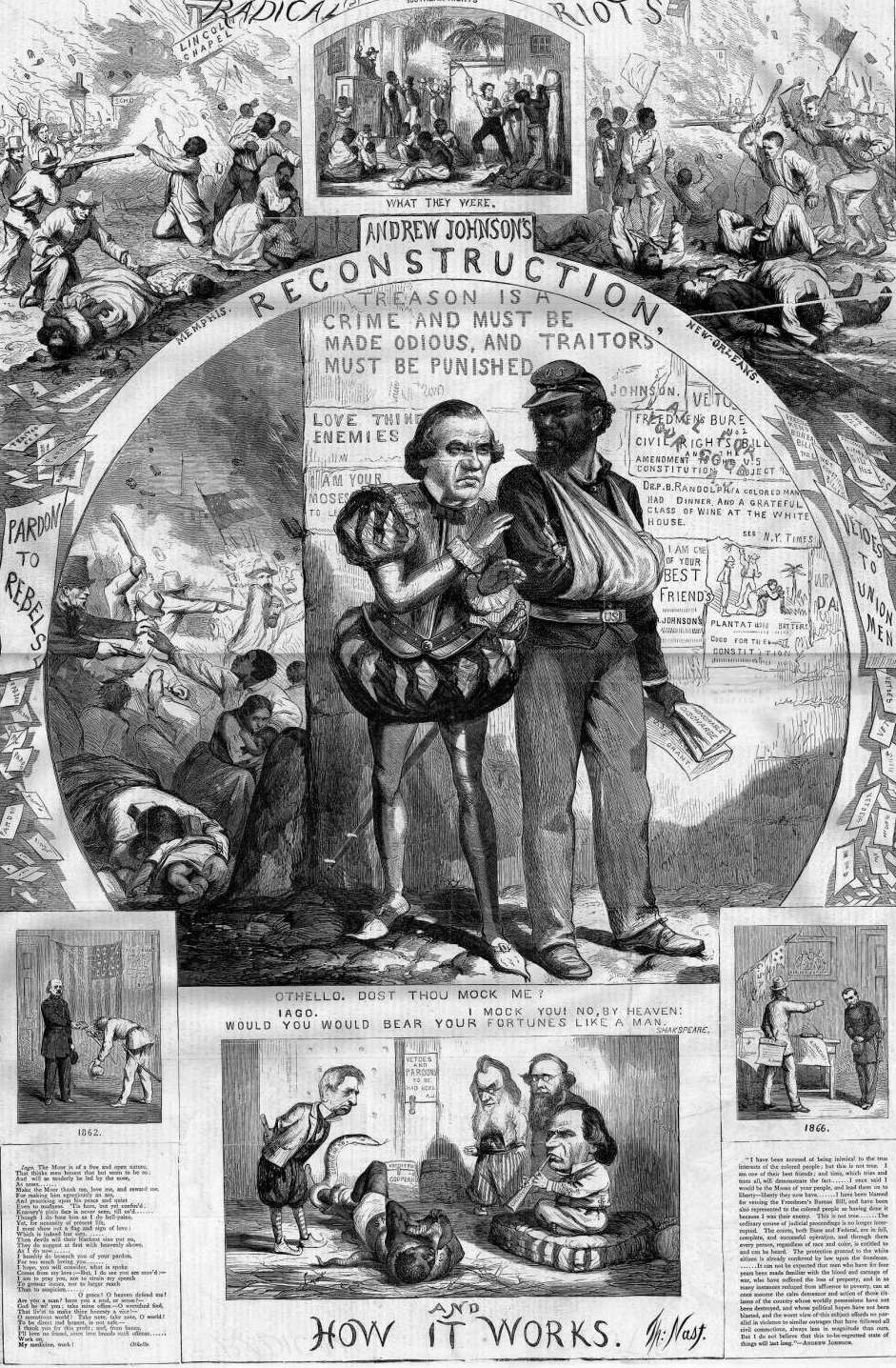

Nast, Thomas, Artist. Andrew Johnson's reconstruction and how it works / Th. Nast. , 1866. September 1. Photograph. Library of Congress

Landmark Amendments to the Constitution

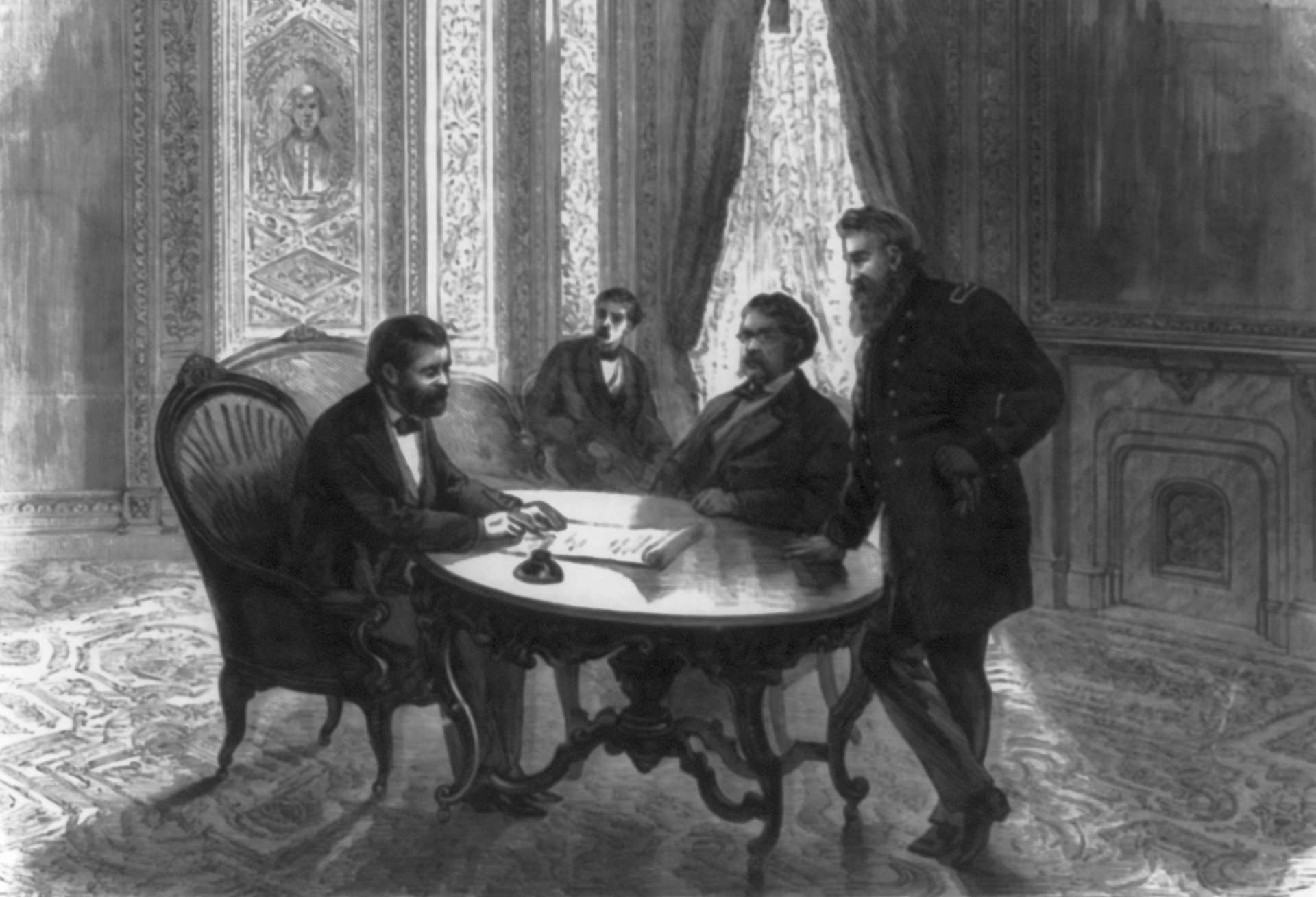

Outraged by President Johnson’s actions, the Republicans in Congress took control of Reconstruction policy. In 1866, they overrode Johnson’s vetoes and passed laws protecting the freedom and rights of formerly enslaved people. In 1867, they passed the Reconstruction Acts, laws which gave Black men in the South the right to vote.

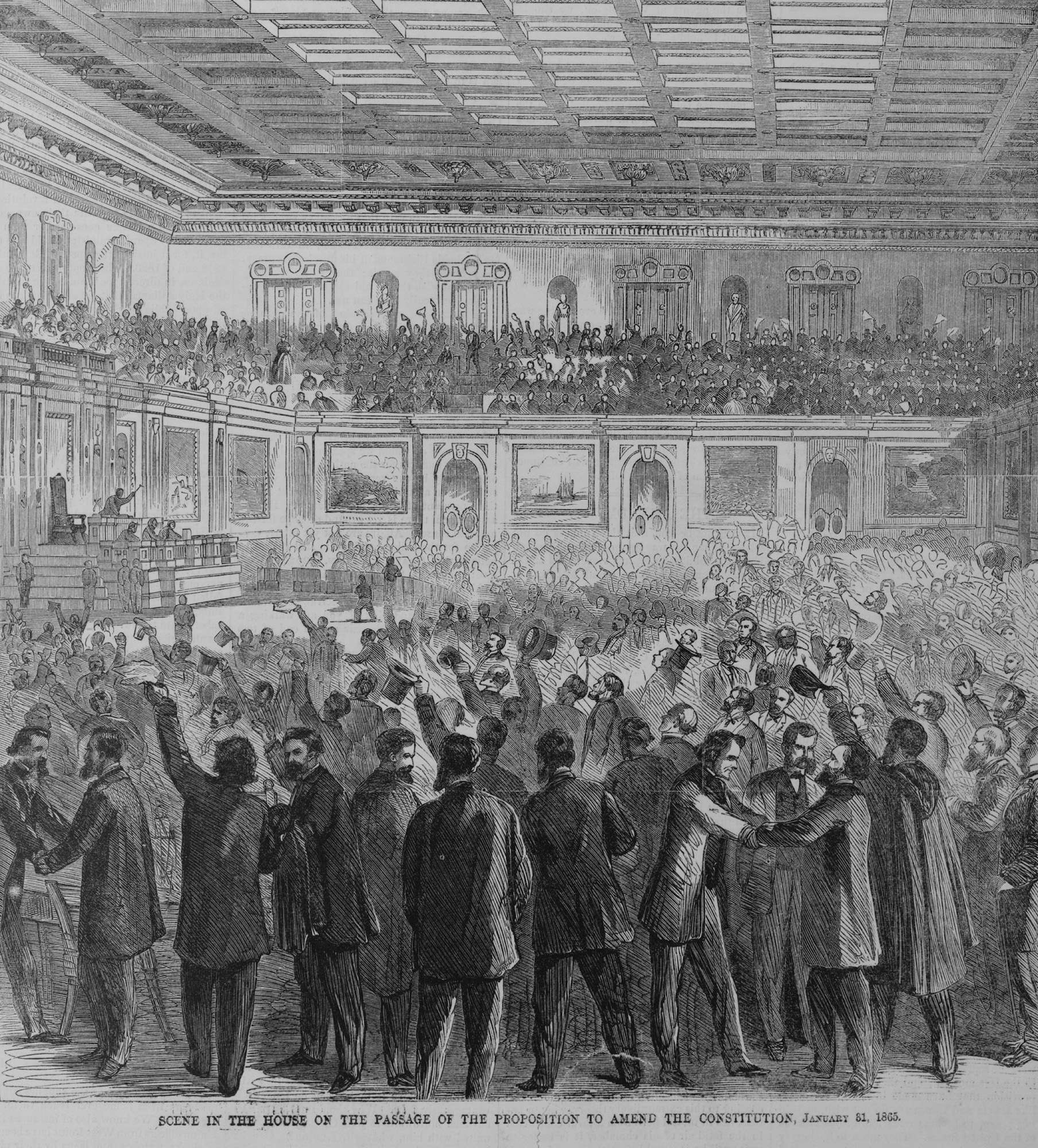

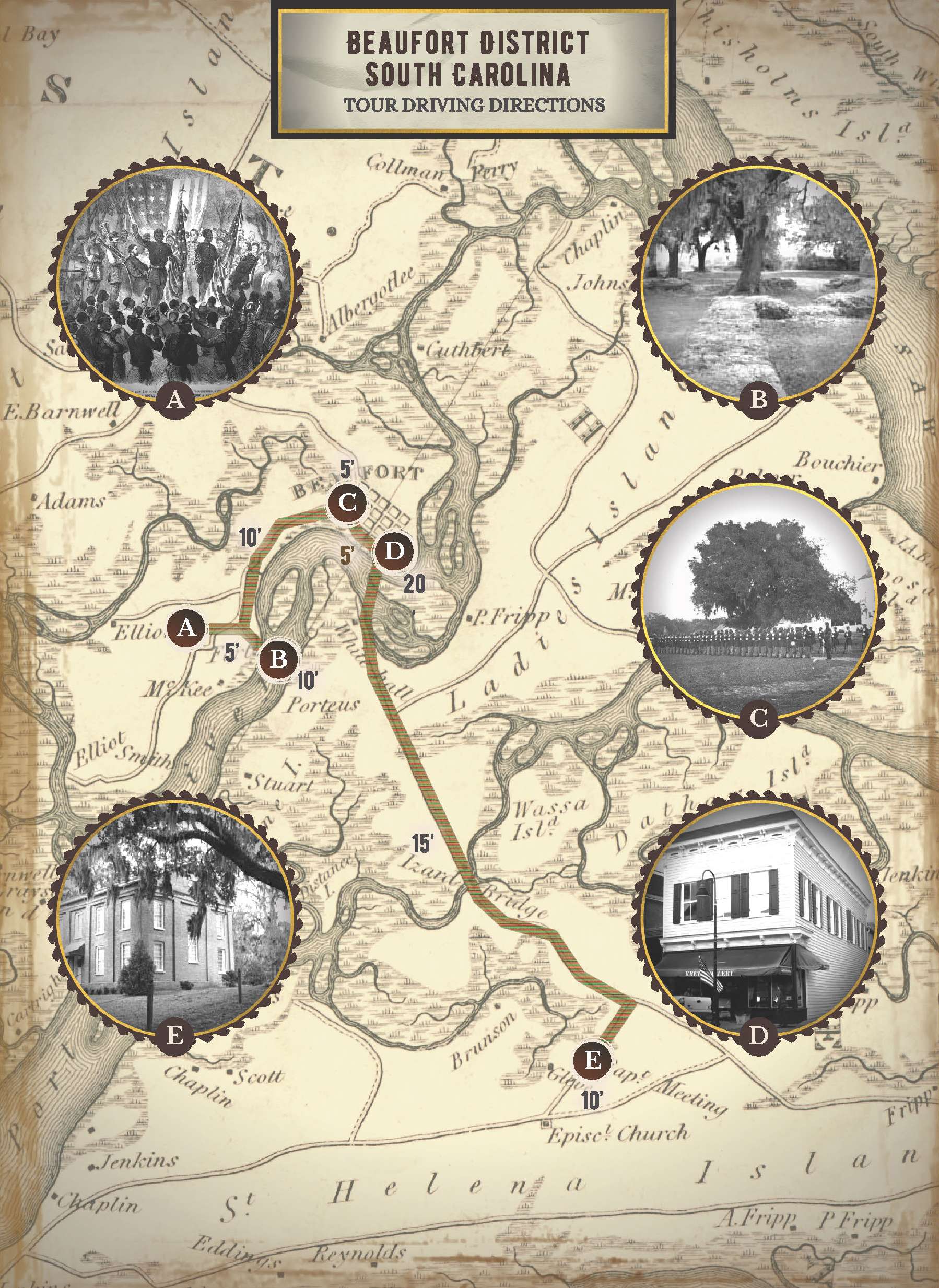

Scene in the House on the passage of the proposition to amend the Constitution. , 1865. Photograph. Library of Congress

Republican-controlled Congresses also passed three amendments to the U.S. Constitution, expanding the civil and political rights of freedpeople and all Americans. The Thirteenth Amendment ended slavery permanently across the entire nation, including areas Lincoln had exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation. The Fourteenth Amendment declared anyone born in the United States, except Native Americans living on reservations, American citizens, regardless of their race. It also promised due process and equal treatment under the law to all persons in the United States. The Fifteenth Amendment barred racial discrimination in the right to vote. All three amendments explicitly gave Congress the power to enforce their provisions. This meant that the federal government had a new obligation to protect individual rights.

Kelly, Thomas, Active. The Fifteenth amendment. , ca. 1870. N.Y.: Published & printed by Thomas Kelly, 17 Barclay St. Photograph. Library of Congress

New biracial state governments in the South translated broad principles of racial equality into new laws and state constitutions. In South Carolina in 1868, a constitutional convention was held under federal military supervision. Able to vote for the first time, three-fifths of the delegates were Black men. The constitution they ratified was the most democratic in the state’s history, abolishing property ownership as a requirement for voting, giving some rights to women, and making public schools open to all races.

The White Southern Backlash

The advances in African American rights and freedoms brought by Reconstruction proved threatening to many Southern whites. The backlash was severe and long-lasting.

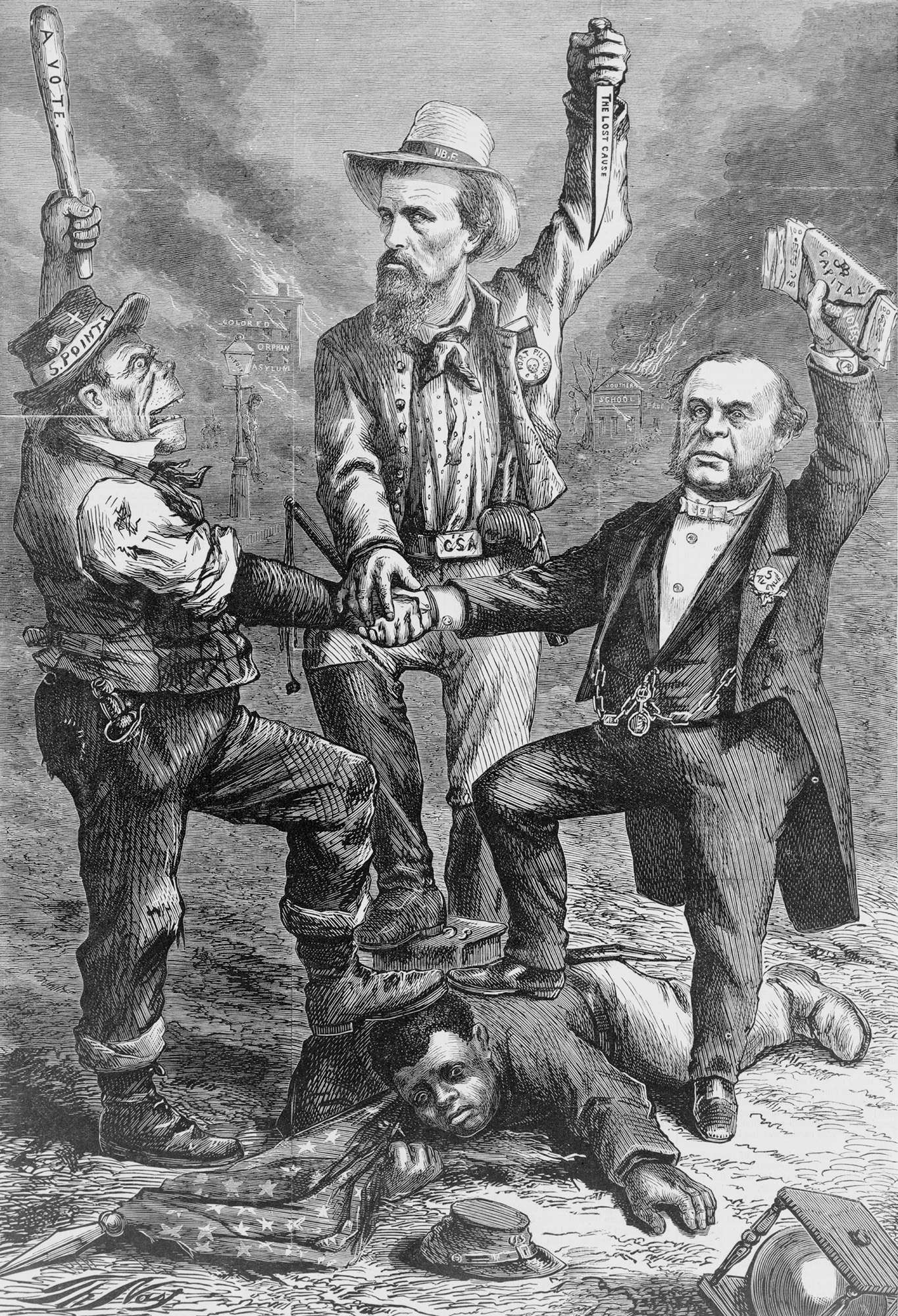

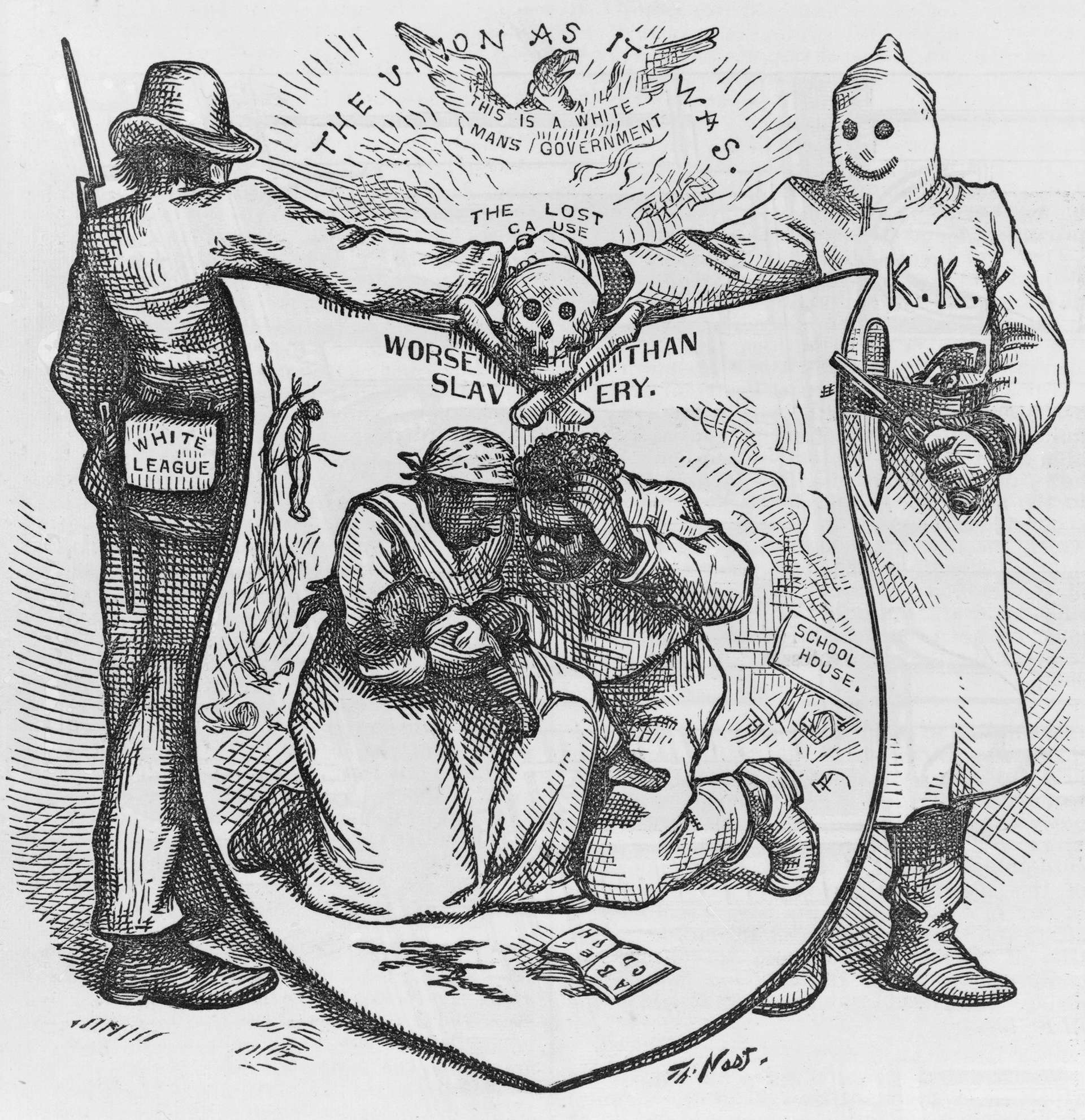

Nast, Thomas, Artist. "This is a white man's government" "We regard the Reconstruction Acts so called of Congress as usurpations, and unconstitutional, revolutionary, and void" - Democratic Platform / Th. Nast. United States, 1868. Photograph. Library of Congress

Angry white Southerners worked to undermine federal policies. The Ku Klux Klan and other white terrorist militias emerged in many locations. They menaced and, in many cases, killed African Americans and their white allies. President Grant and the federal government took measures to counteract the violence, such as passing the Ku Klux Klan Act in 1871. This made conspiracies to deprive people of their constitutional rights a federal crime and sent troops into South Carolina to crush the Klan. The U.S. troops who remained in the South were busy protecting Republican-controlled state legislatures and Black elected officials from being violently overthrown. Black militias that had formed while Republicans were in power were forced to stand down and relinquish their weapons in many places. This left most freedpeople more vulnerable to labor exploitation, intimidation, and white mob violence.

Washington, D.C. - President Grant signing the Ku-Klux Force Bill in the President's room with Secretary Robeson and Gen. Porter, at the Capitol, April 20, 1871. Photograph. Library of Congress

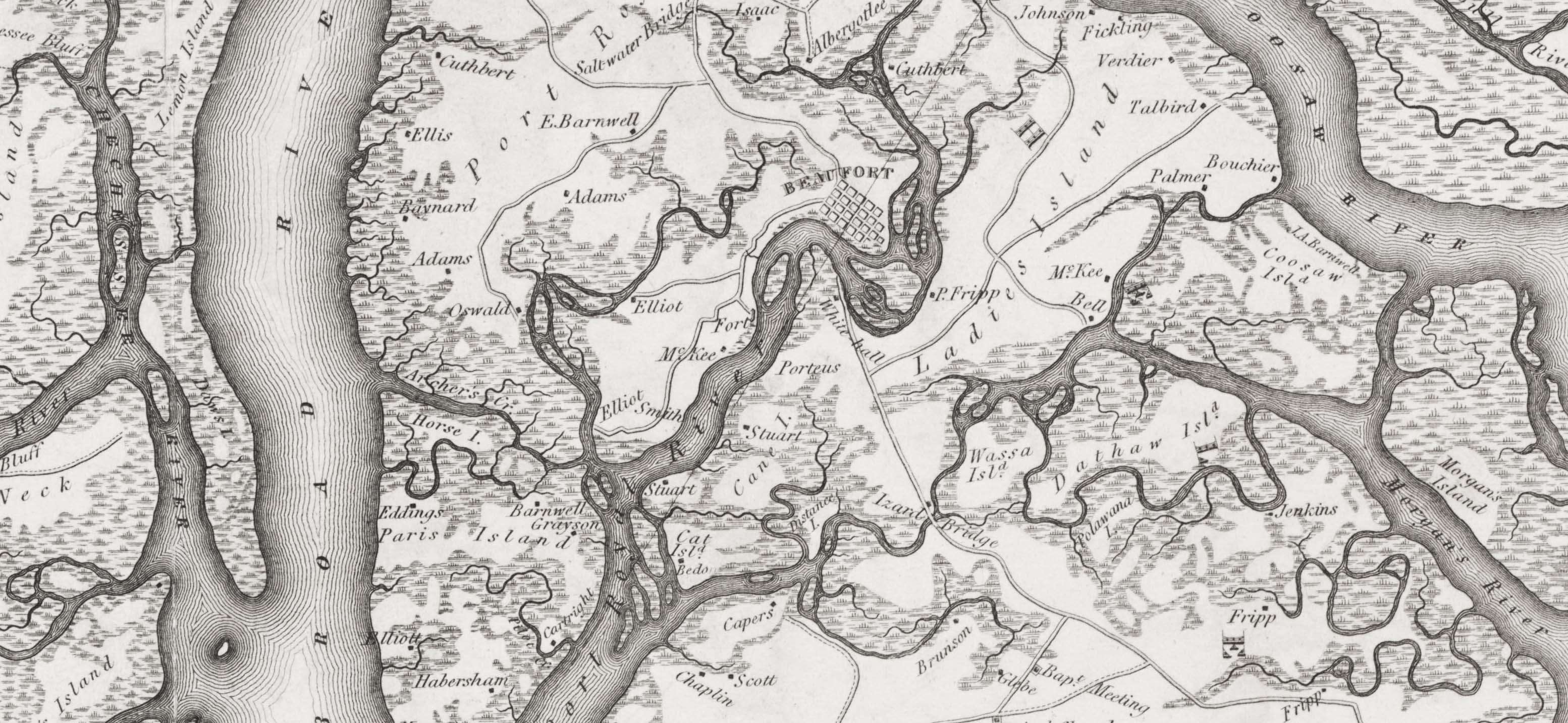

In the Sea Islands, however, African Americans were able to maintain more autonomy and make steady progress for several years. By 1877, South Carolina’s white supremacist Democrats were wrestling control of the state back from the Republican and African American officials who had been elected during Reconstruction. In November, State Adjutant General Moise came to Beaufort County to inspect what remained of the Black militia. He ordered them to disband and return their arms to the Arsenal. But most of the men bravely refused, keeping their weapons and later agreeing to reorganize under new leadership.

App Stop

In the Free & Equal mobile app, you can relive this unique resistance to Jim Crow in Beaufort’s arsenal. An augmented reality animation on top of an old photograph of the Arsenal shows how this resistance went down. Check it out by downloading the app and going to chapter 10.

To download the mobile app visit freeandequalproject.com

In an 1878 case brought by Robert Smalls, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that freedpeople who had bought property in the Sea Islands Direct Tax Auctions could keep it. Smalls continued to hold political office long after most Black elected officials had been removed. In his speech at the 1895 South Carolina Constitutional Convention, where white politicians aimed to disfranchise Black men through a variety of new voting laws, he made an impassioned plea:

Let us make a Constitution that is fair, honest and just. Let us make a Constitution for all the people, one we will be proud of and our children will receive with delight.

The North Looks Away

Support in the North for Reconstruction and for protecting the rights of African Americans weakened in the 1870s. While Northern Republicans wanted to preserve Reconstruction, Northern Democrats were eager for its end. Many white Northerners in both parties believed that Black people were innately inferior to white people. After the economy collapsed in 1873, public opinion shifted toward the Democrats’ view. Northerners grew more sympathetic to white Southerners’ complaints about the continuing presence of U.S. soldiers in the South and federal “interference” with their white supremacist agenda. Socialist movements in Europe and labor agitation across several U.S. industries sparked fears of worker uprisings. Many white Northerners began to see freedpeople’s demands for better labor conditions as dangerous and “un-American.”

The Great Financial Panic of 1873. Photograph. Library of Congress

Many white Americans wanted to move past the war and heal a divided country. Federal officials were unable or unwilling to prevent white Southerners from denying African Americans the rights guaranteed under the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments.

Nast, Thomas, Artist. The Union as it was The lost cause, worse than slavery / / Th. Nast. , 1874. Photograph. Library of Congress

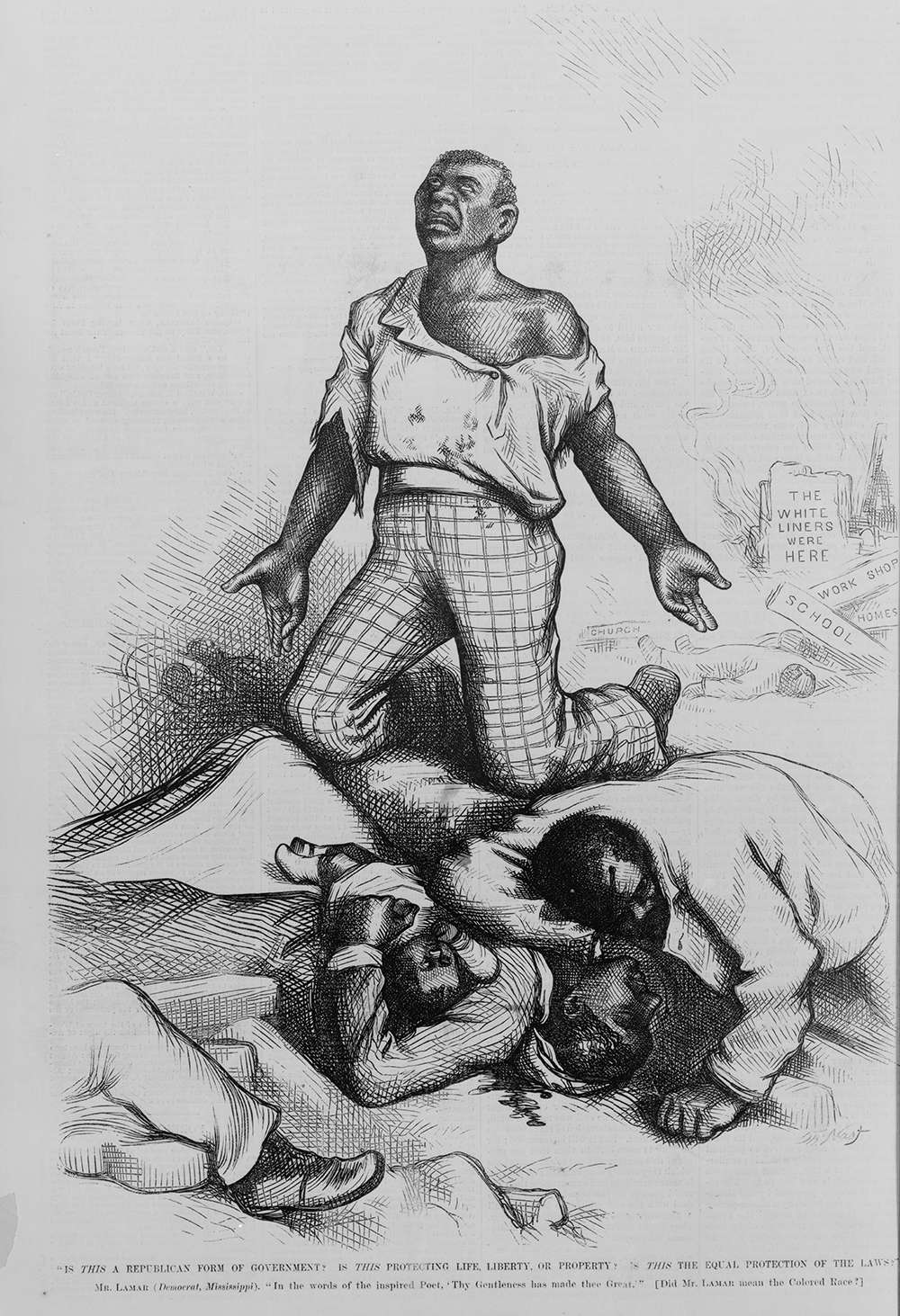

After the presidential election of 1876, the federal government removed most of the remaining federal troops from the South. Southern Democrats proceeded to use all means at their disposal – including fraud and terrorism – to stop Black men from voting and win control of state governments. Over the course of the next generation, Southern state governments passed laws designed to permanently disenfranchise African Americans. They also instituted harsh segregation policies that separated and excluded Black citizens from schools, hospitals, streetcars and trains, public parks, funeral homes, and many other important services.

Nast, Thomas, Artist. Is this a republican form of government? Is this protecting life, liberty, or property? Is this the equal protection of the laws? / Th. Nast. , 1876. Photograph. Library of Congress

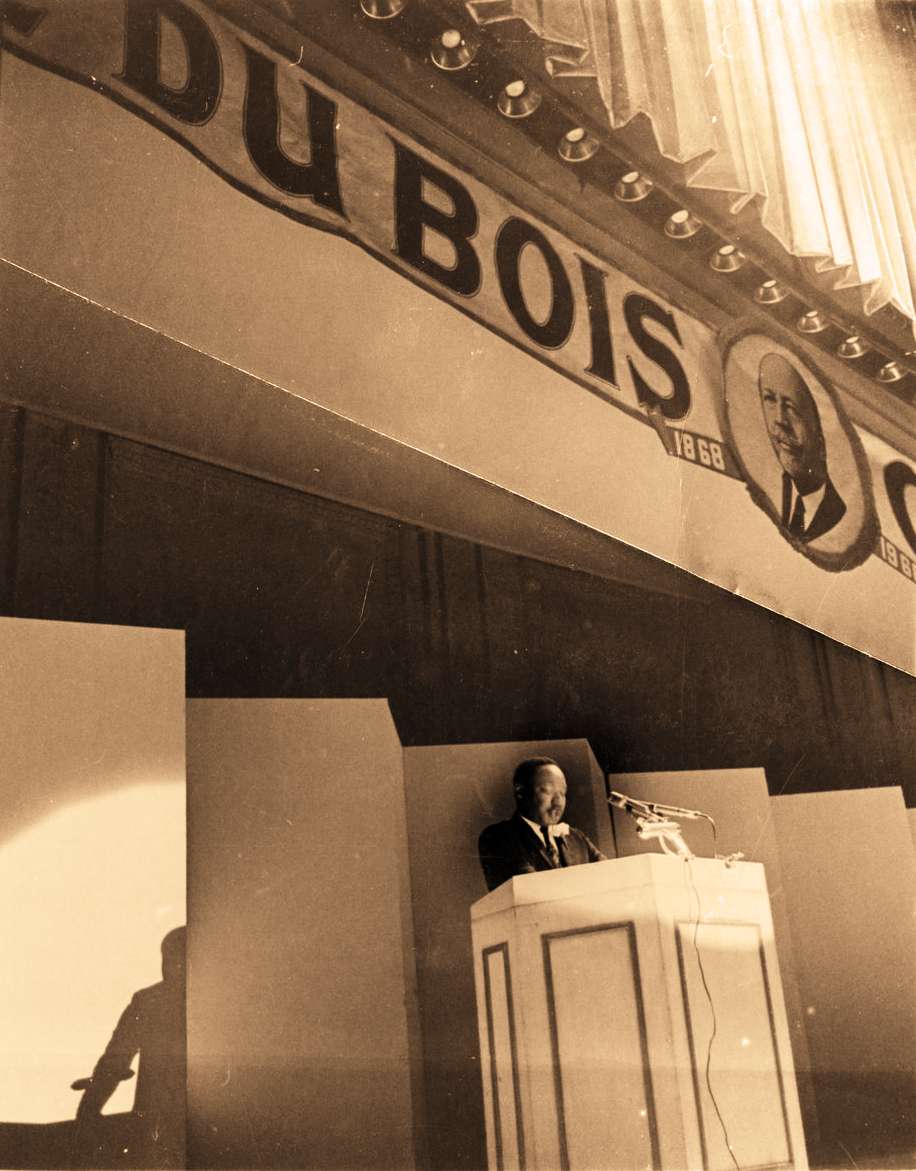

“The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”

Segregation Becomes the Law of the Land

The U.S. Supreme Court helped solidify the end of Reconstruction with a series of rulings in the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s. In The Civil Rights Cases decision of 1883, for example, the court ruled that under the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, Congress could not prohibit a private individual or company from discriminating against people based on their race. In the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, the court reaffirmed that segregation was legal as long as accommodations for white and Black people were “separate but equal.” In reality, they rarely were equal. In Williams v. Mississippi (1898), the court undermined the Fifteenth Amendment, allowing local election officials to use literacy tests and other means to keep Black men from exercising the right to vote.

Harper's Weekly, vol. 23 (1879 Jan. 18), p. 52. The color line still exists - in this case. Illustration. Library of Congress

By the end of the century, Reconstruction’s advances toward a biracial democracy were mostly erased. The Southern states were entirely under the control of the white elite, including descendants of planters who had ruled before the war. Segregation, separation, and disenfranchisement became the law in every Southern state by 1908. These practices would largely stand until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Despite the nation’s failure to live up to the promises laid out in the Reconstruction Amendments, African Americans would continue to fight for decades to exercise their basic rights. With determination and resourcefulness, freedpeople and those who came after them made lasting gains, providing a foundation for future generations.

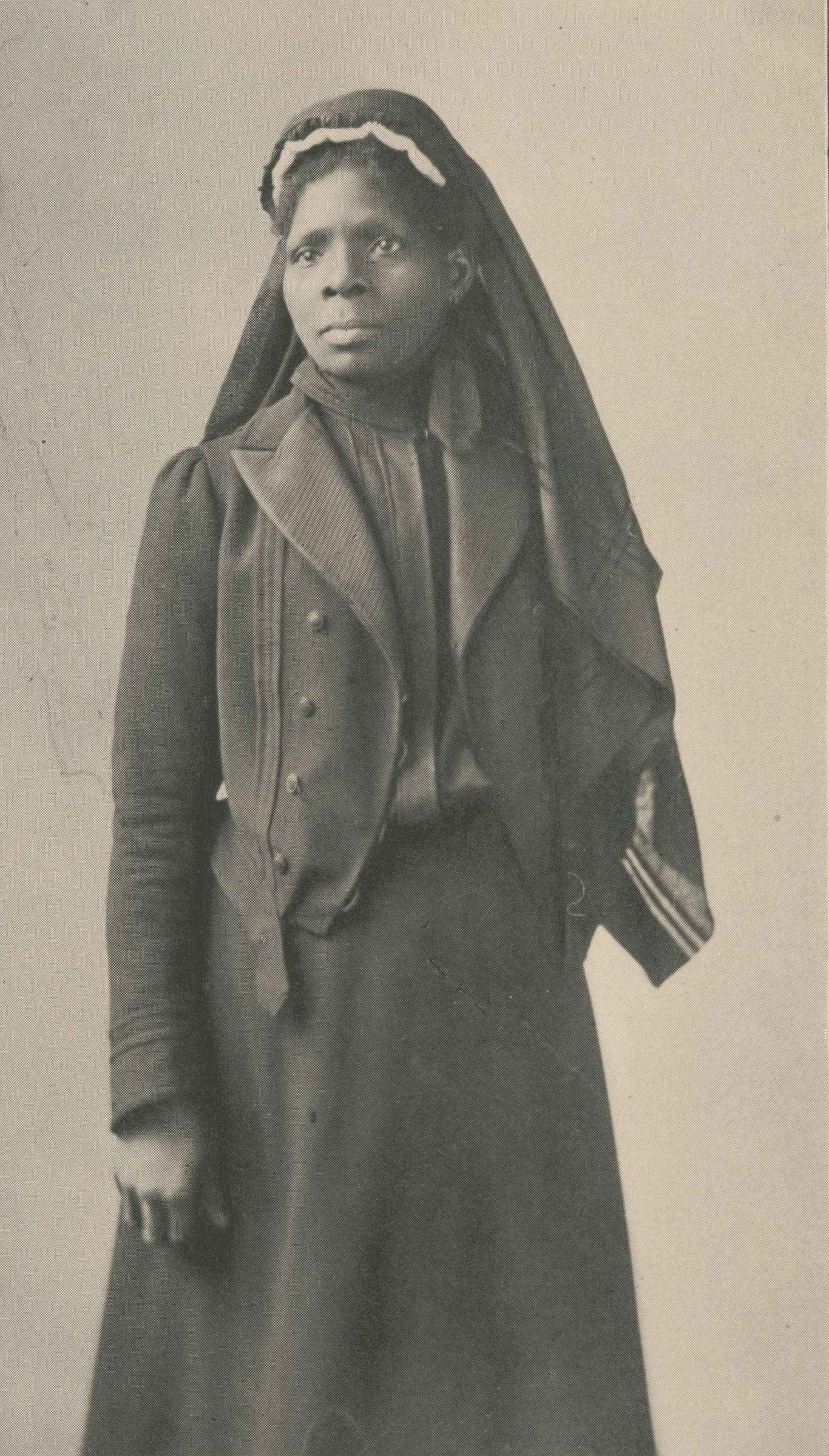

Susie King Taylor reflected on Reconstruction’s mixed results in her memoir, published in 1902:

What a wonderful revolution! In 1861 the Southern papers were full of advertisements for ‘slaves,’ but now, despite all the hindrances and ‘race problems,’ my people are striving to attain the full standard of all other races born free in the sight of God, and in a number of instances have succeeded. Justice we ask, to be citizens of these United States.

Next Chapter

Conclusion

Freedpeople of the Sea Islands struggled to realize the civil rights that all Americans deserve today, yet many still struggle to achieve.