Freedom

Emancipation was a long struggle, not a gift

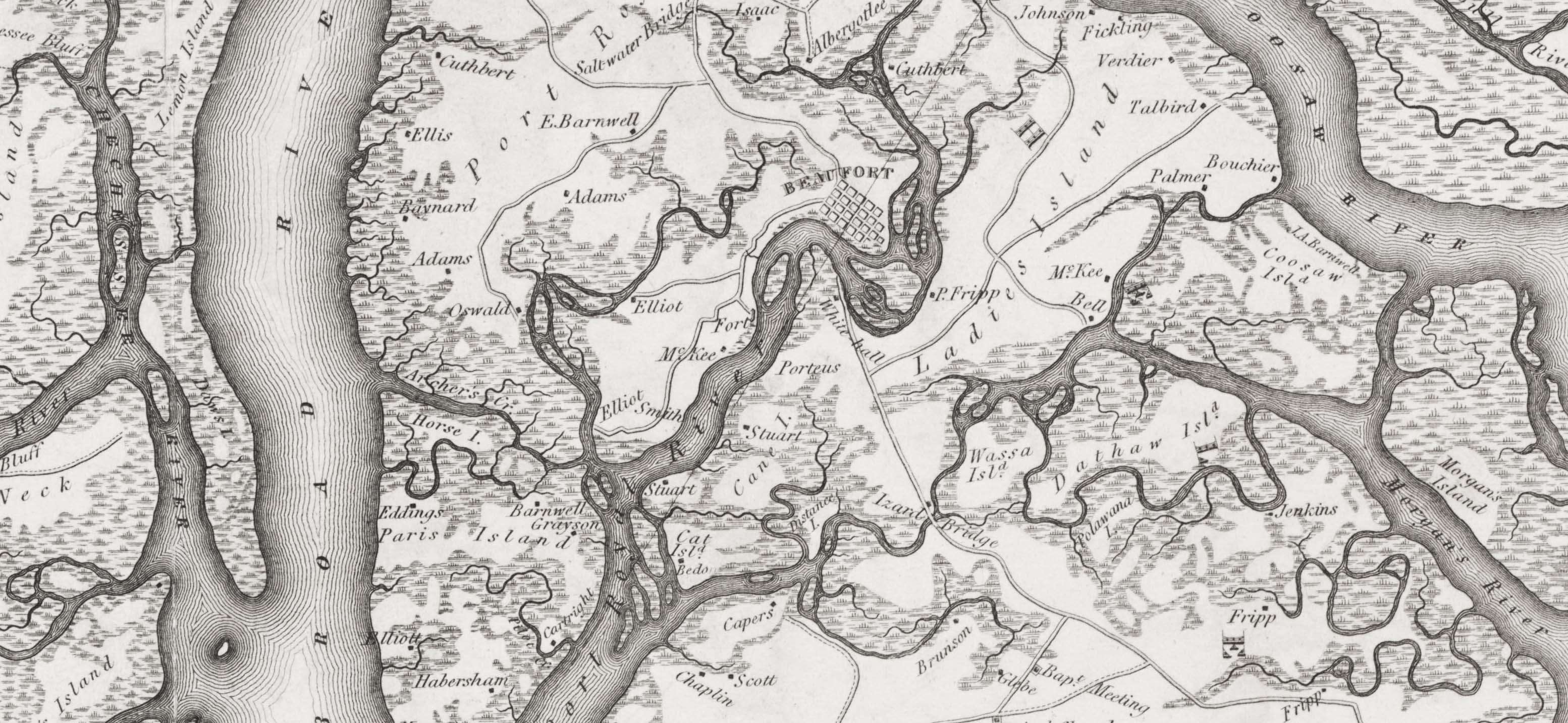

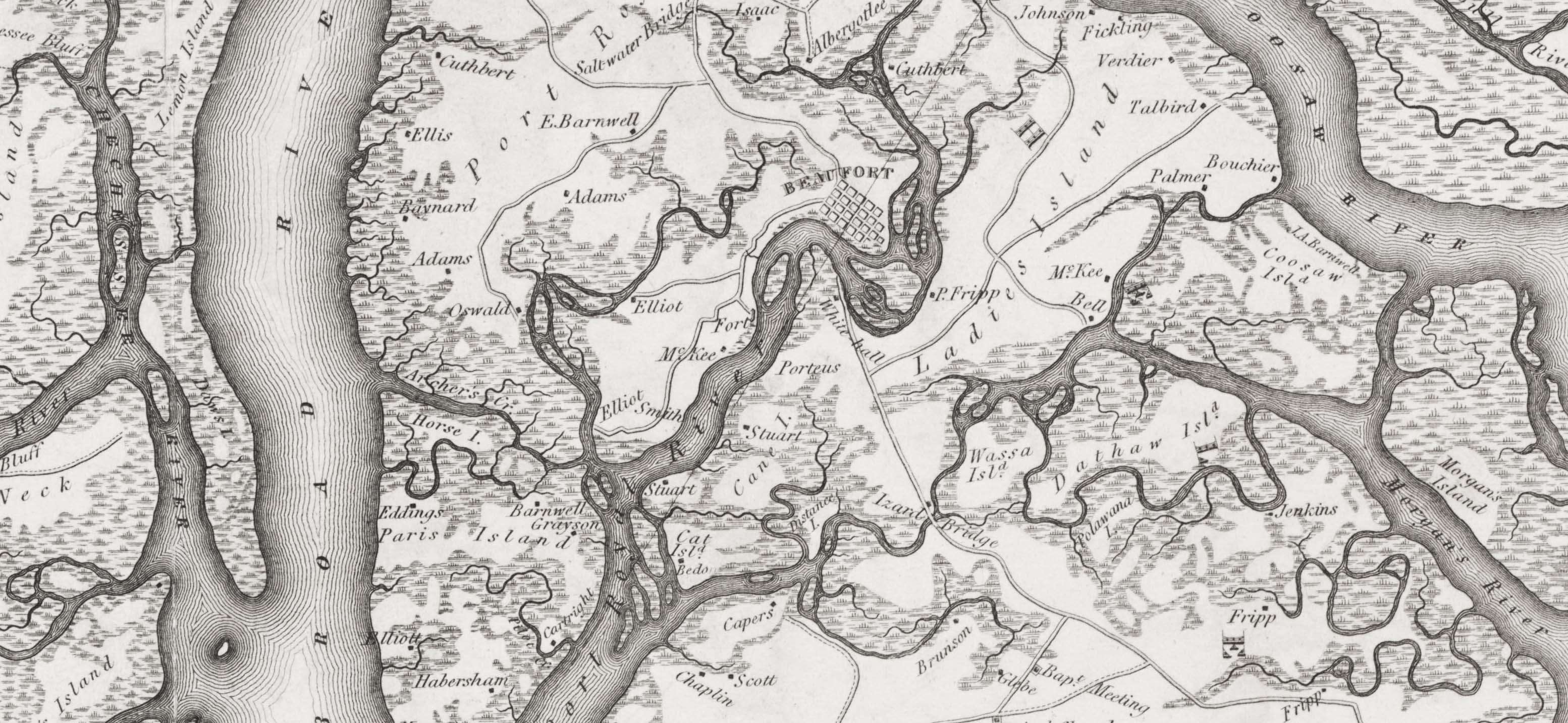

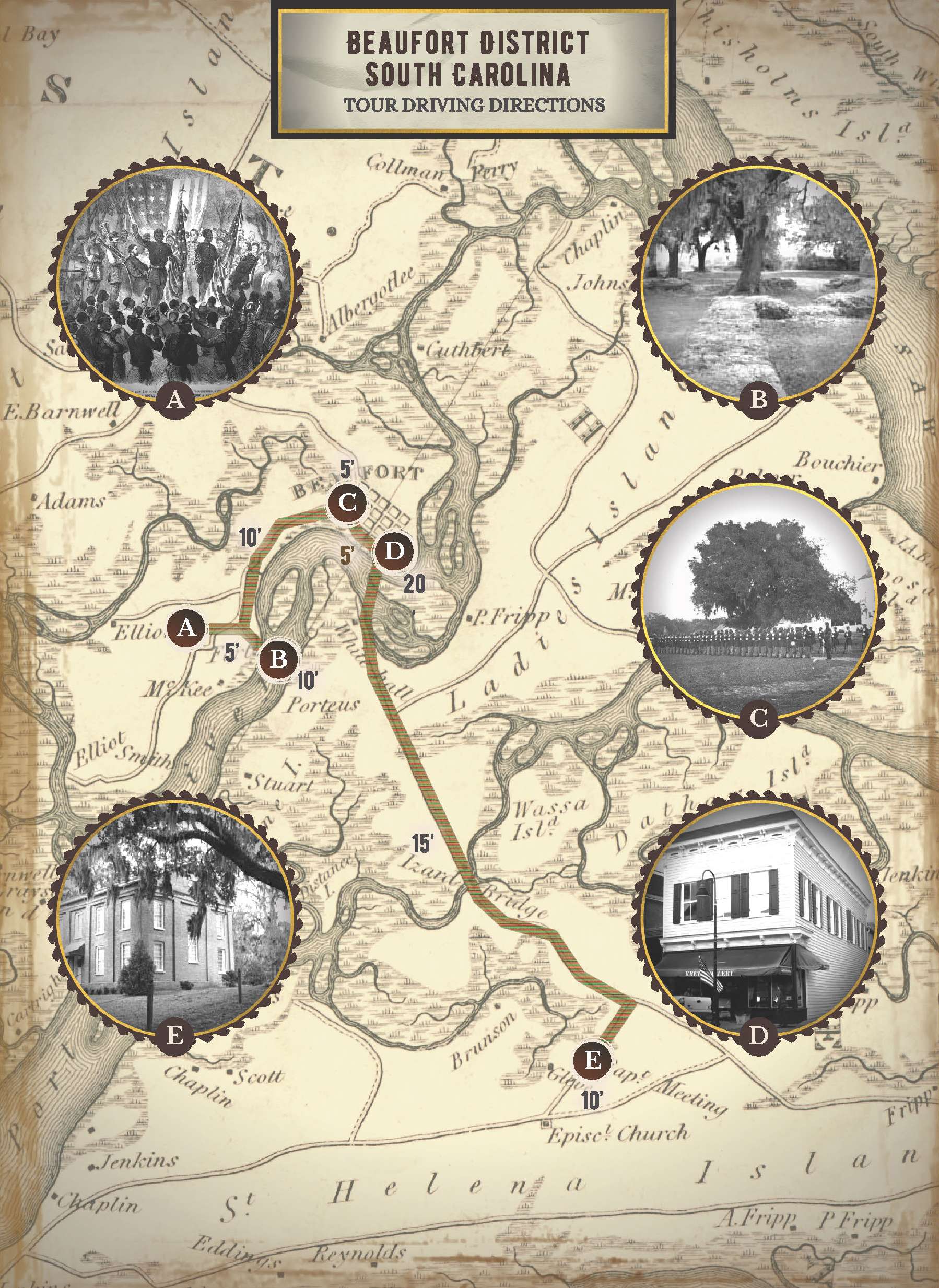

Early in the Civil War, the freedpeople of the Sea Islands took advantage of their freedom to support the war effort.

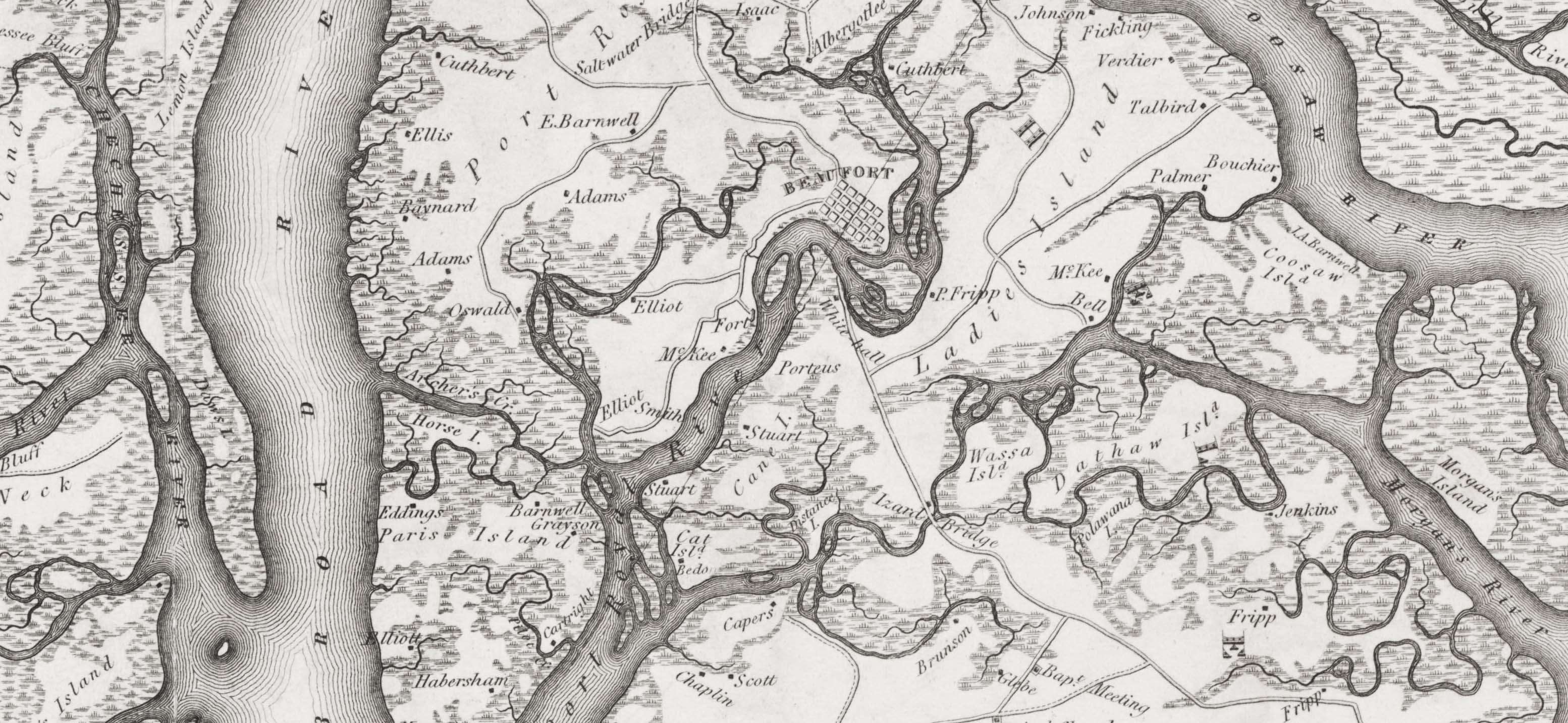

Steamboat pilot Robert Smalls, serviceman Isaiah Browne, and liberator Harriet Tubman leveraged their intimate knowledge of the Sea Islands to free enslaved people and aid the U.S. military's war against the Confederacy.

Freedom as a Military Strategy

Enslaved people had always looked for ways to become free. Some, like Harriet Tubman and the people she helped escape through the Underground Railroad before the war, used their intimate knowledge of the land to navigate northward to free territory. Others found ways to earn money and buy their freedom.

Lindsley, Harvey B, photographer. Portrait of Harriet Tubman. Library of Congress

Negro slaves Edisto Island, S.C. plantation of James Hopkinson. Photograph. Library of Congress

During the war, enslaved people understood that their freedom was at stake. They did everything they could to tip the scales against the Confederacy. They sabotaged cotton production and other supply chains to the Confederate army. They joined the Northern war effort, acting as spies, scouts and support staff in the camps. Perhaps most importantly, they joined up as soldiers.

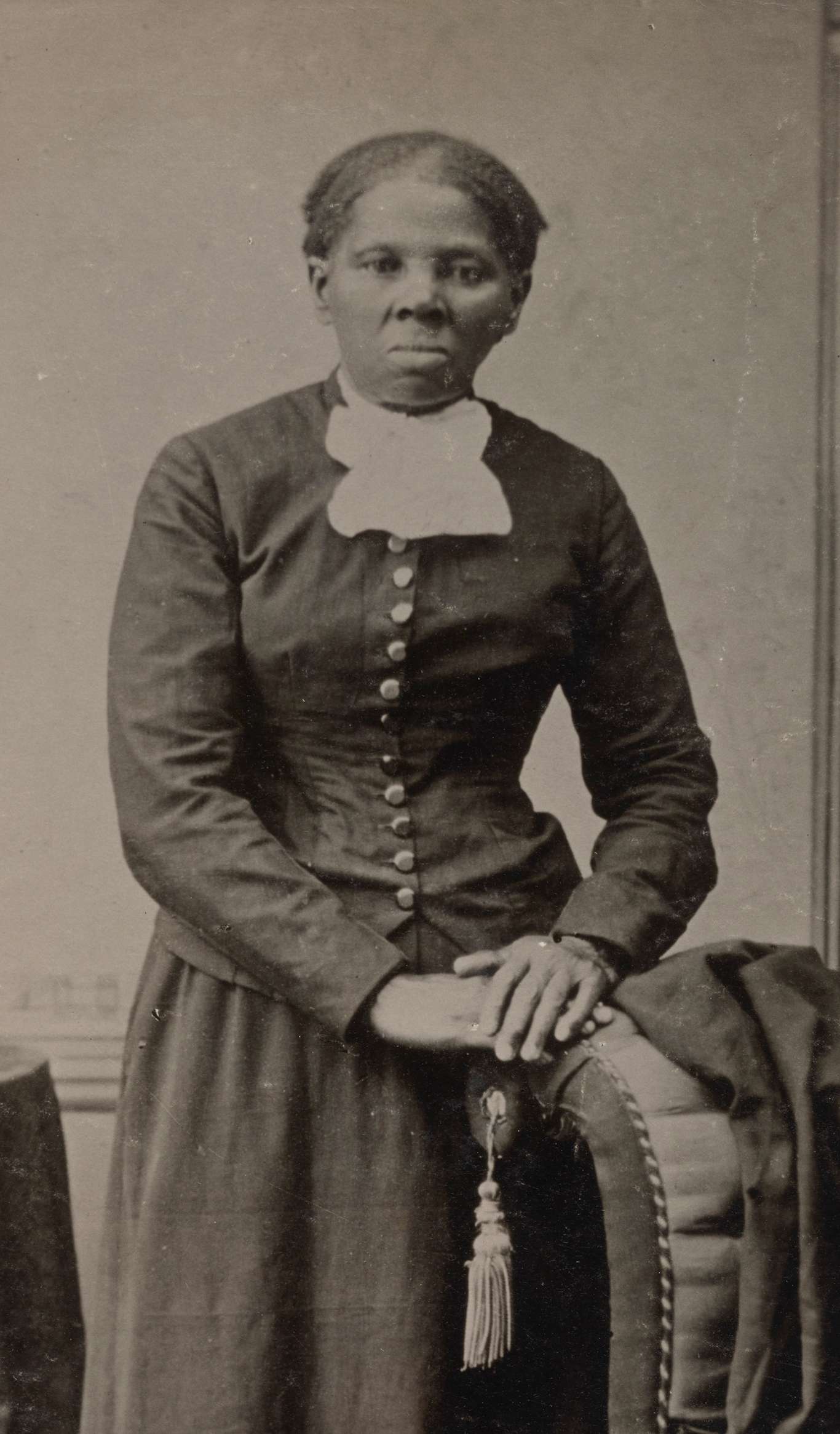

O'Sullivan, Timothy H, photographer. Fort Beauregard, Bay Point, S.C. Nov. Library of Congress

Gen. William T. Sherman encountered a black Georgian who summed up the slaves’ understanding of the war from its outset: “He said … he had been looking for the ‘angel of the Lord’ ever since he was knee-high, and, though we professed to be fighting for the Union, he supposed that slavery was the cause, and that our success was to be his freedom.

O'Sullivan, Timothy H, photographer. Library of Congress

Many enslaved people fled from plantations to nearby U.S. military positions. They formed encampments in many places in the South, including a large one outside of Beaufort. One of them was Susie King Taylor.

Cooley, Sam A, photographer. Ruins of the Old Spanish Fort, Smith's plantation, Port Royal Island, near Port Royal S.C. Photograph. Library of Congress

App Stop

In the Free & Equal mobile app, you can relive an evening at Camp Saxton, replete with Gullah stories, songs, and lessons recited by freedpeople. Stop 6 drives you from Camp Saxton to where the soldiers displayed their new marching skills to awestruck white Union soldiers.

To download the mobile app visit freeandequalproject.com

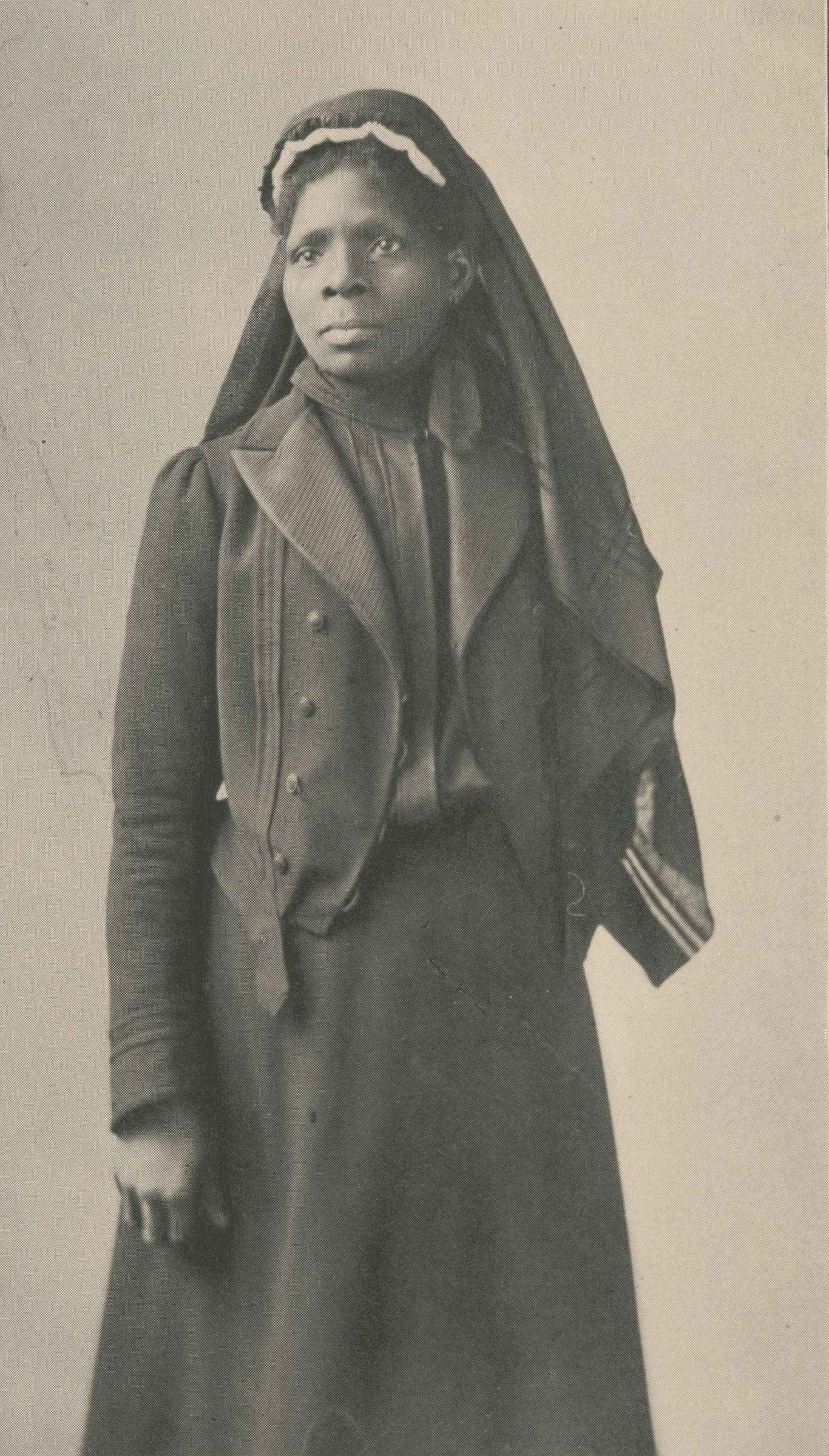

Susie King Taylor

Susie King Taylor fled her enslavers in Darien, Georgia, in the spring of 1862. She sought refuge on a U.S. gunboat near Fort Pulaski and arrived in Beaufort that October. As a child, she had been secretly educated and could read and write. Her skills made her indispensable to the military officers she met in the encampment. Later she married a freedman named John King who enlisted in the 1st South Carolina Volunteer regiment.

Susie King Taylor, known as the first African American Army nurse. Library of Congress

Taylor, Susie King. Reminiscences of my life in camp with the 33d United States colored troops, late 1st S. C. volunteers, / by Susie King Taylor. United States, 1902. Boston. Photograph. Library of Congress

I learned to handle a musket very well while in the regiment, and could shoot straight and often hit the target. I assisted in cleaning the guns and used to fire them off, to see if the cartridges were dry, before cleaning and reloading, each day. I thought this great fun. I was also able to take a gun all apart, and put it together again.

Freedpeople Support the War Effort

Formerly enslaved people’s persistent presence at the military camps pushed the question of their status to the front burner. U.S. military leaders in the field and political leaders in Washington D.C. had to decide how to respond to their demands for protection and freedom. These wartime interactions significantly influenced Reconstruction policies to come.

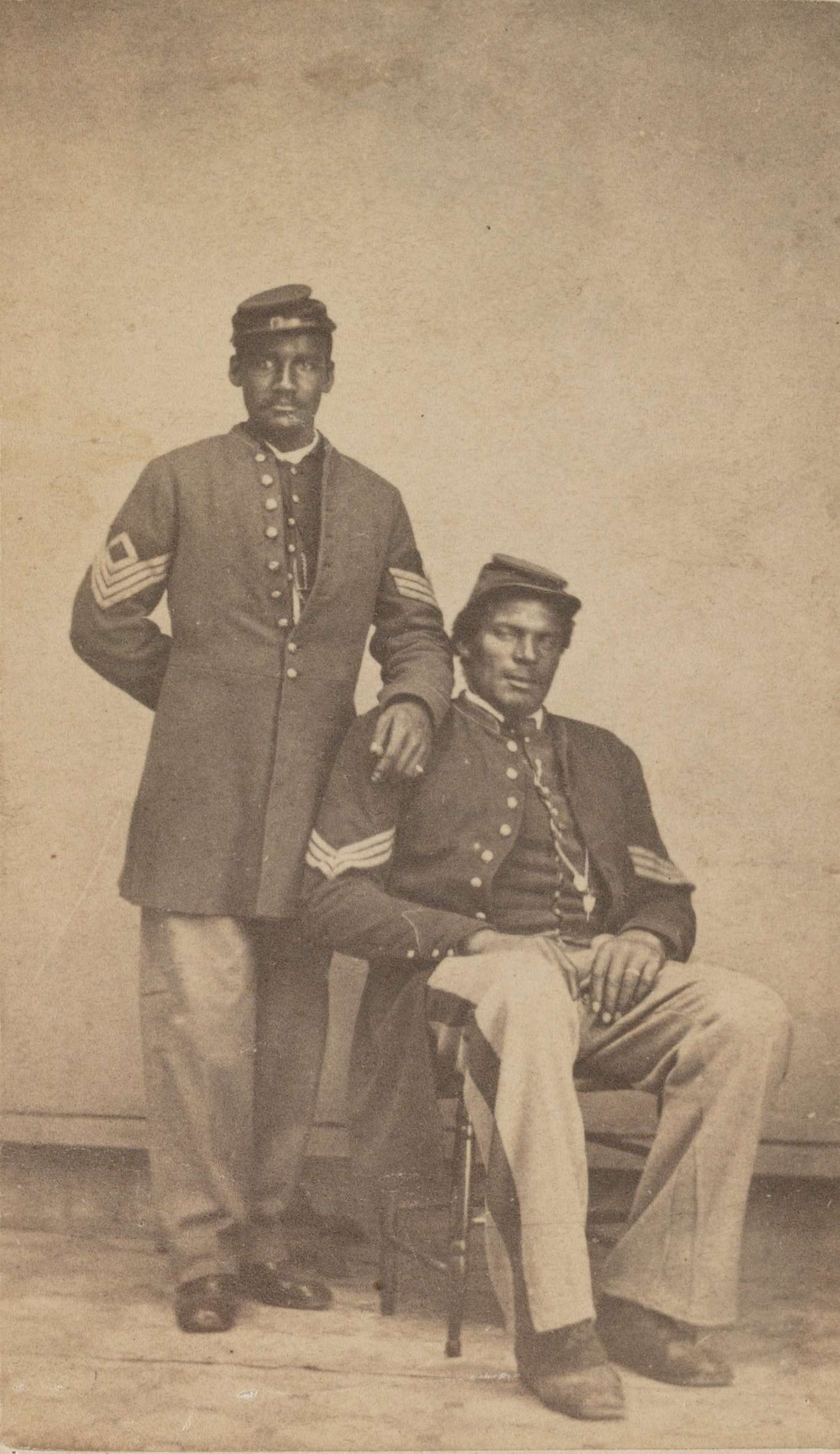

Two unidentified African American soldiers in Union sergeant's uniforms. Library of Congress

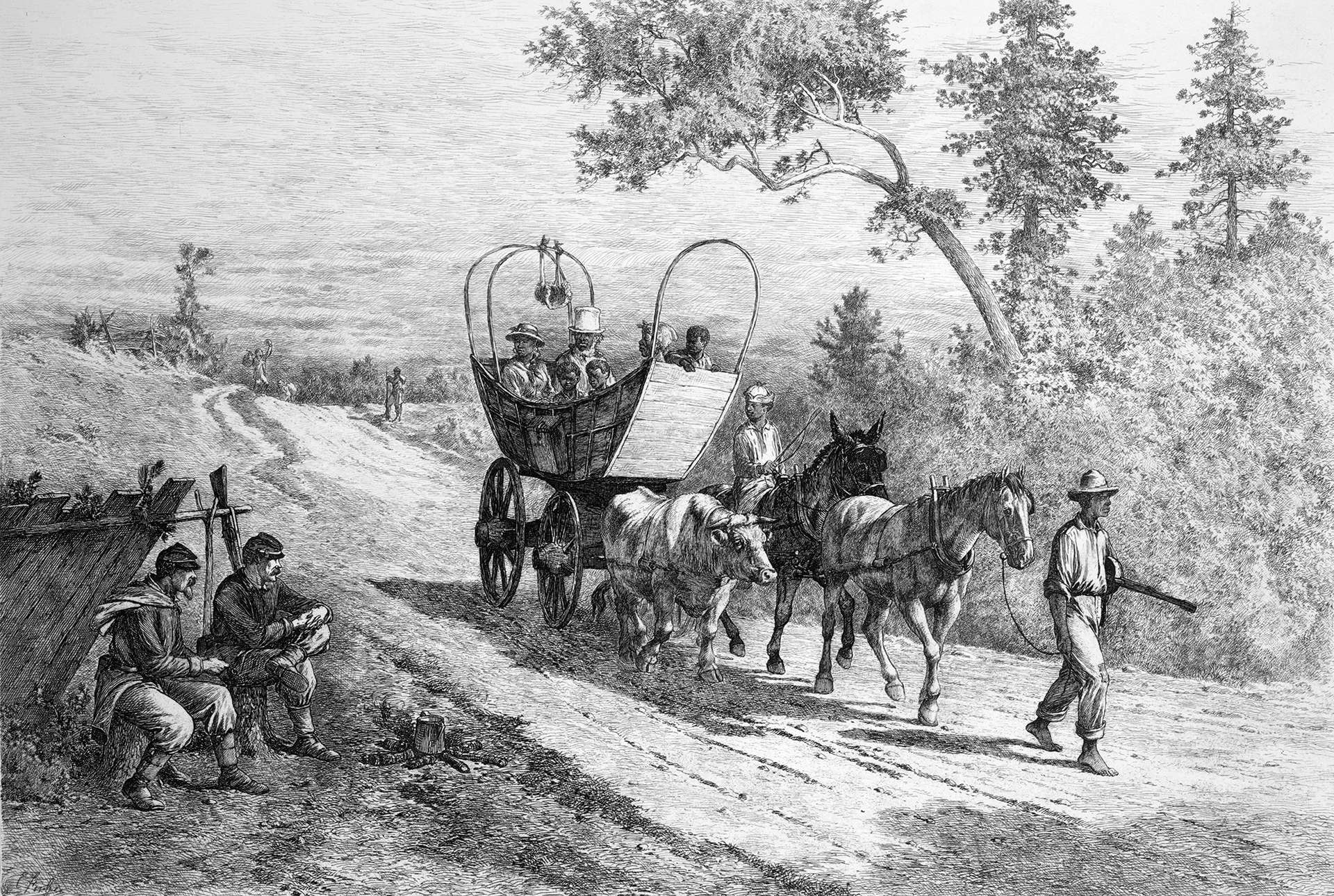

Returning the self-emancipated people to their enslavers would help the Confederate war effort, so that was not a viable option. In many cases, the military decided to employ the refugees as camp laborers, sometimes forcing them to work without pay. Like Susie King Taylor, women often served as laundresses. Both men and women worked for the armed forces as teamsters, hostlers, and cooks. They also produced cotton and food, operated as spies on and off the battlefield, and helped to disrupt Confederate operations.

Forbes, Edwin, artist. Fugitive Slaves Escaping to Union Lines, 1864. Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora

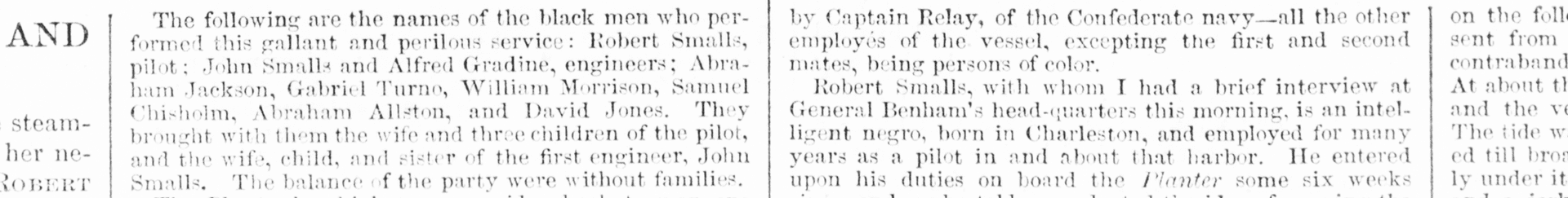

Robert Small's Escape

Enslaved people took great risks to both free themselves and aid the U.S. war effort.

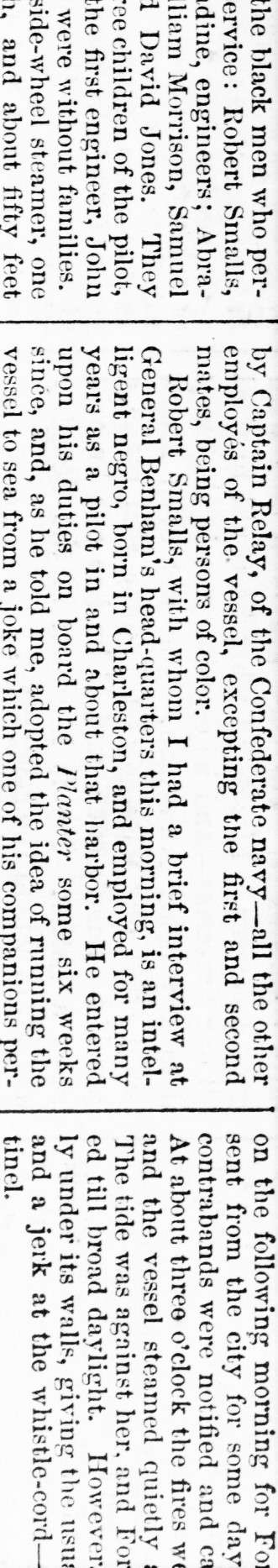

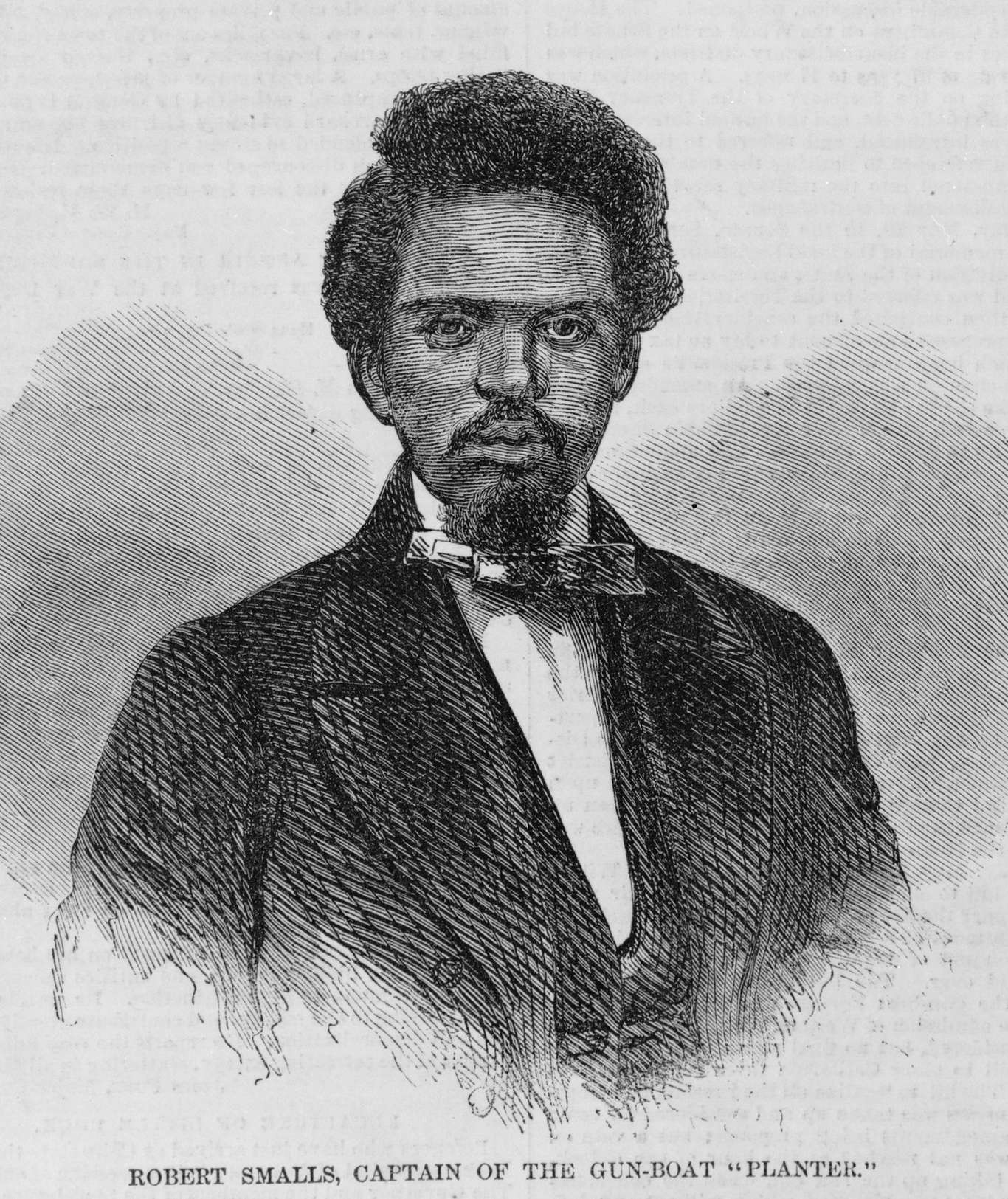

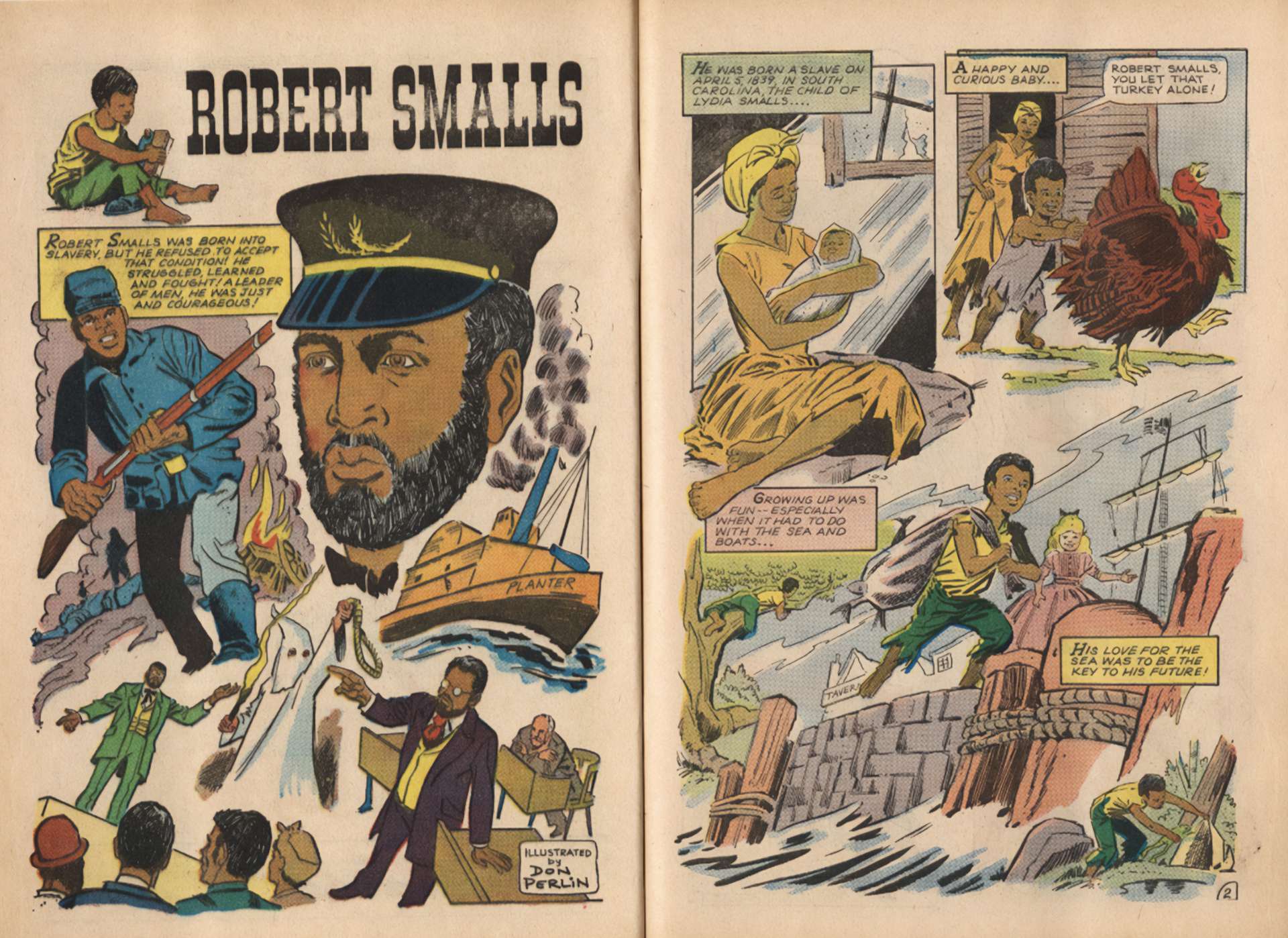

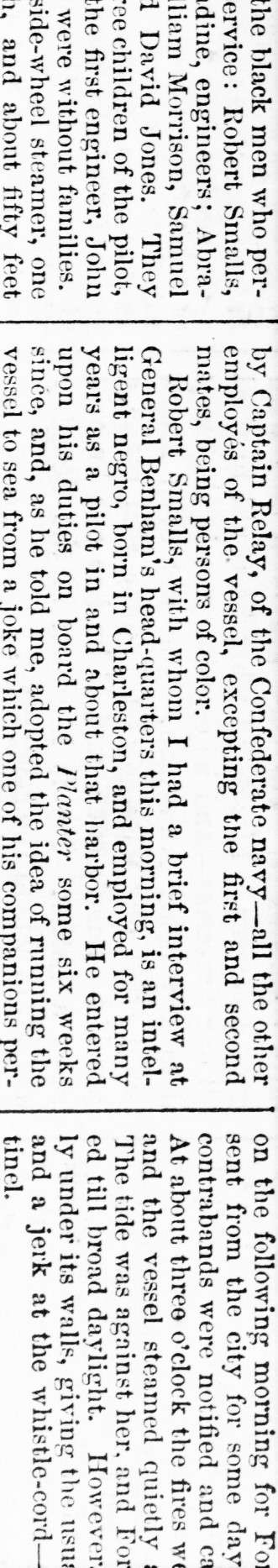

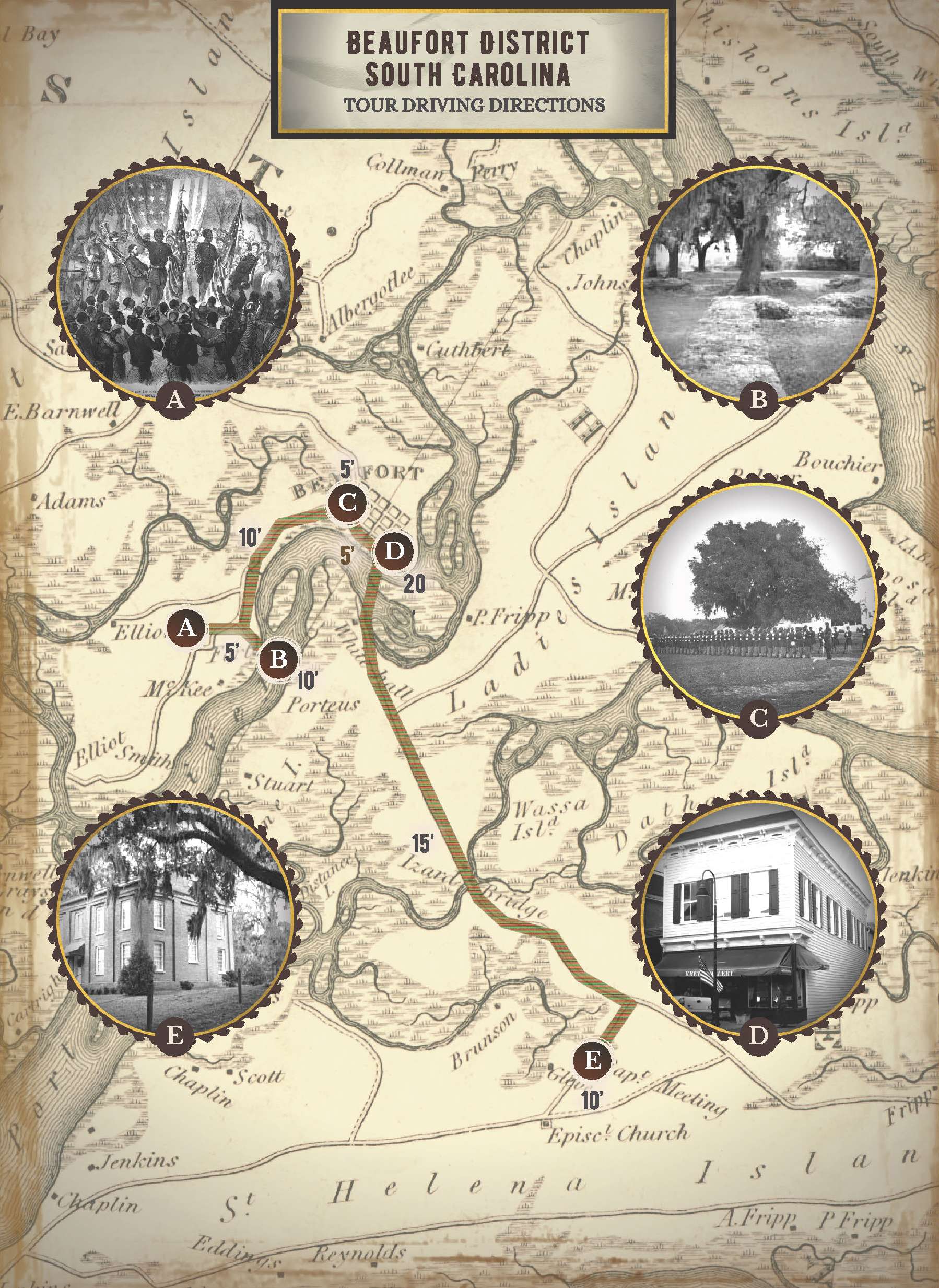

Take, for example, enslaved steamship pilot Robert Smalls. Smalls was born in Beaufort in 1839, and spent his youth enslaved as a house servant in the home of his enslaver, Henry McKee. When Smalls was a teenager, McKee hired him out to a variety of waterfront jobs in Charleston. After the war broke out, the Confederates hired the Planter, the steamboat on which Smalls had become pilot.

Perlin, Don. Artist. Golden Legacy Illustrated History Magazine, The Life of Robert Smalls. 1970. Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

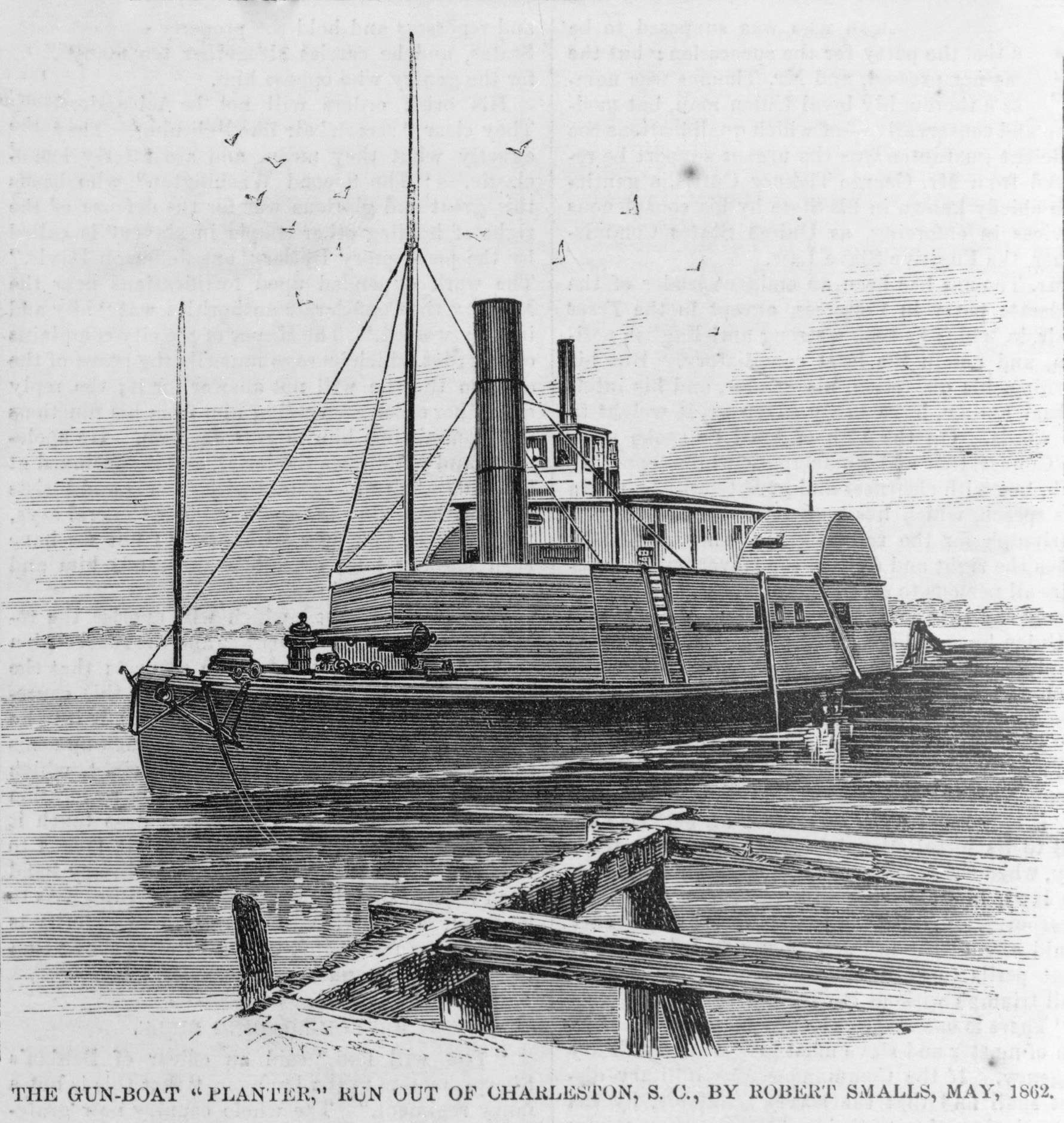

The gun-boat “Planter." Photograph Library of Congress

On May 12, 1862, Smalls sailed away under cover of darkness with sixteen other enslaved people, including his wife and daughters. The Planter was carrying weapons meant for Confederate forces. Smalls disguised himself as the captain and steered the ship out of Charleston Harbor, stopping along the way to sneak his passengers aboard. Outside the harbor he raised a sheet as a white flag and approached a U.S. Navy vessel, offering the weapons in exchange for protection for himself and his passengers. The crew gained their freedom and a sizeable reward from the federal government, of which Smalls received $1,500.

As a free man, Robert Smalls bought the house of his former enslaver. Historic American Buildings Survey Public Domain

App Stop

In the Free & Equal mobile app, you can relive the capture of the Planter by Robert Smalls on a free "character card” you get from the National Park site. Augmented reality brings his daring theft to life in animation and dramatic readings. Stop 5, download the app now to check it out.

To download the mobile app visit freeandequalproject.com

Volunteer Soldiers Become Servicemen

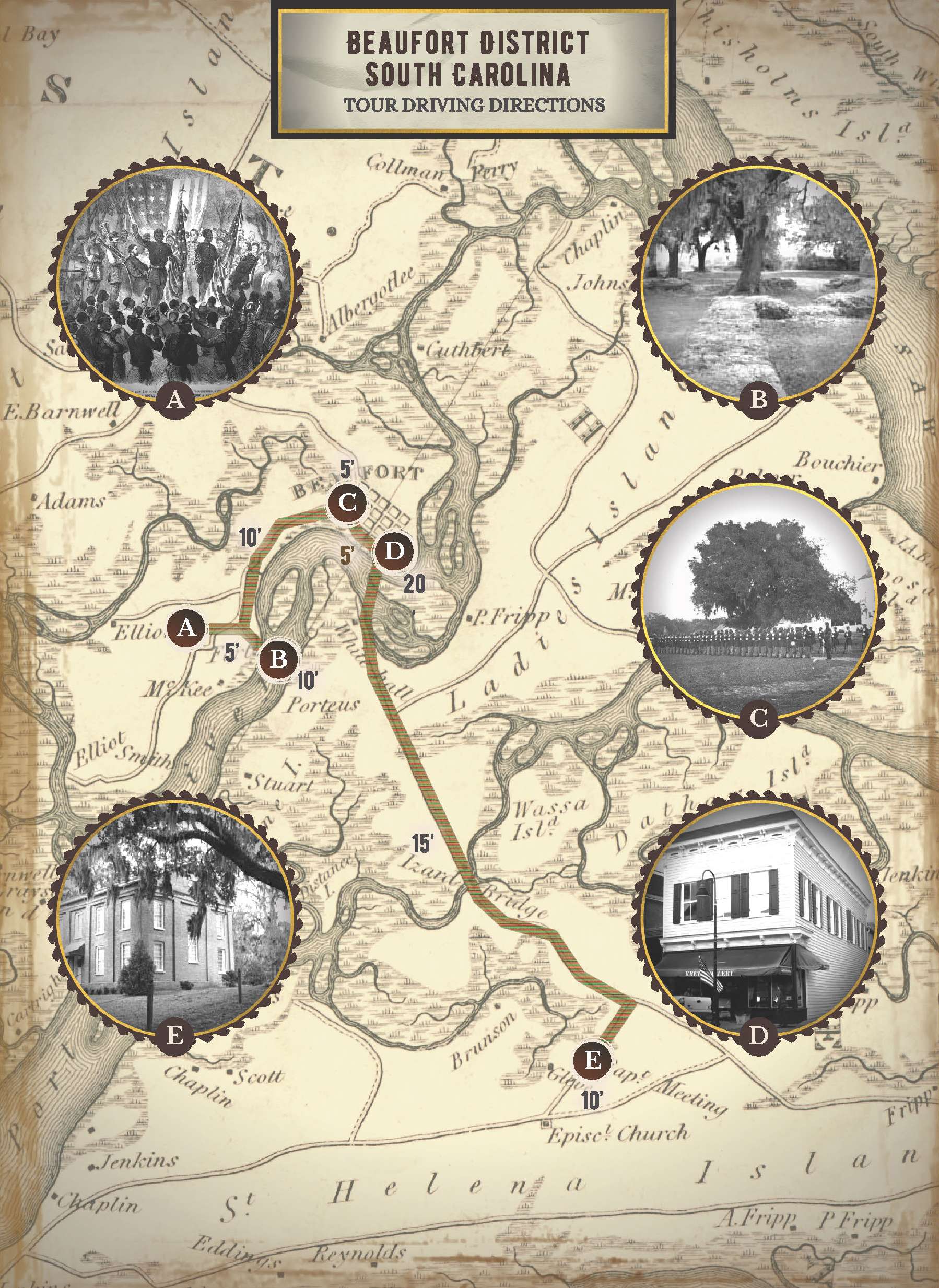

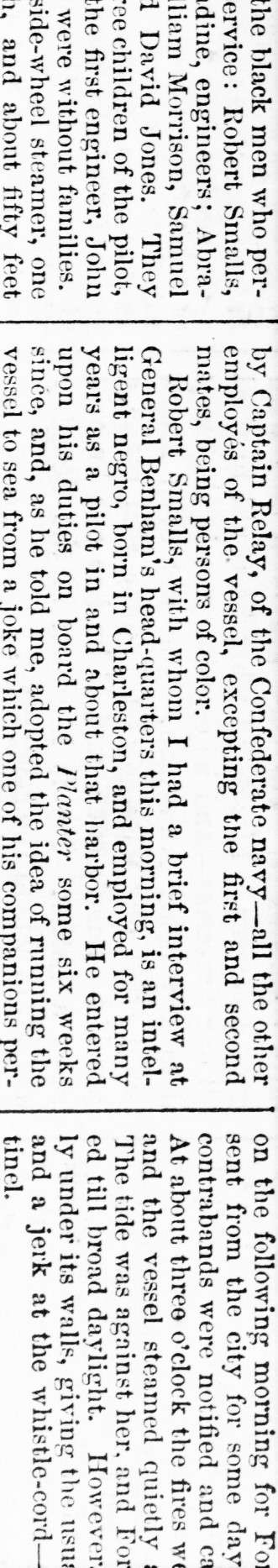

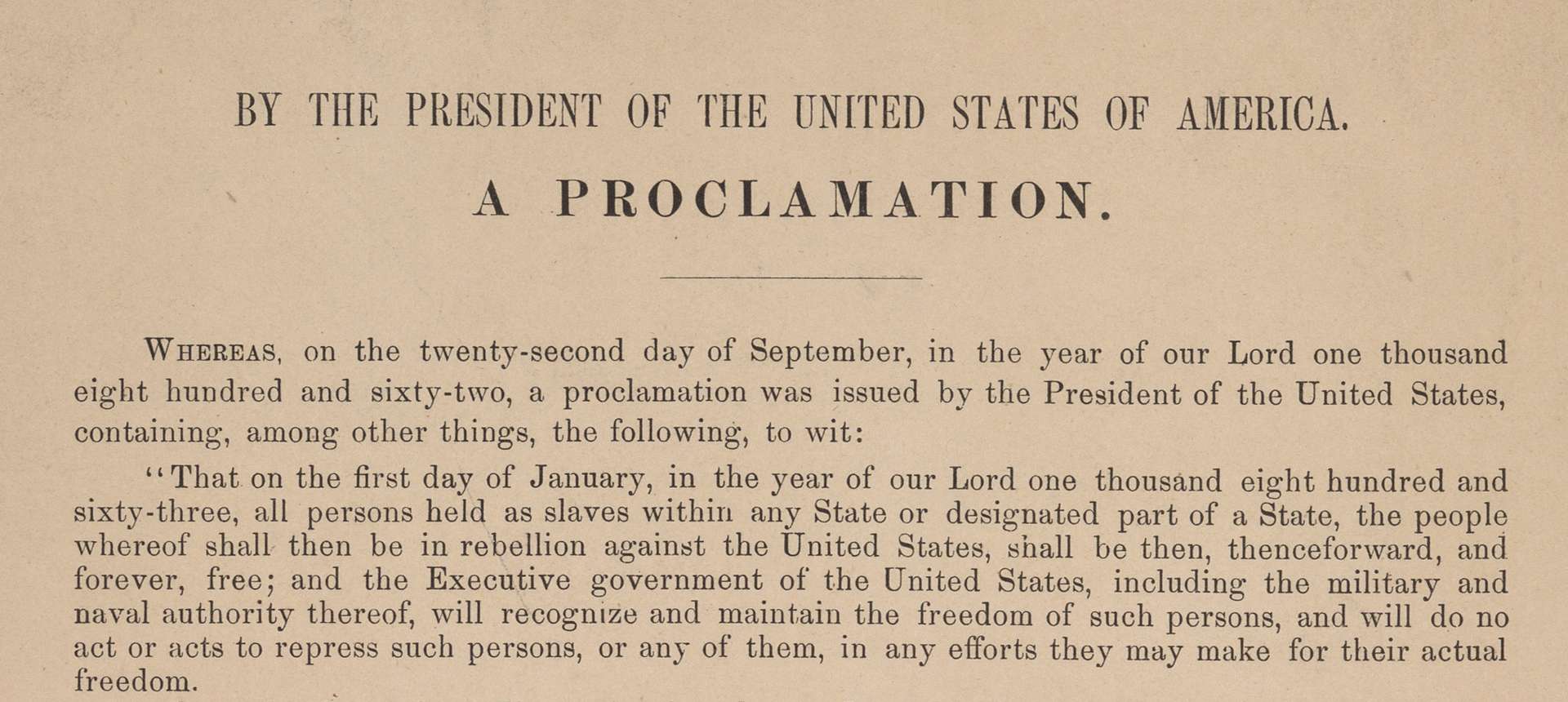

Black men could not officially enlist as soldiers until after the Emancipation Proclamation in January of 1863. But volunteer regiments composed mostly of freedmen participated in the fighting before then. In the Sea Islands, Major General Hunter decided in April of 1862 to arm freedmen who had volunteered for service. Isaiah Brown and his brothers were among those who immediately joined up and received weapons and uniforms.

Cooley, Sam A, photographer. First Sergeant Luther Hubbard of Co. C, 26th U.S. Colored Troops Infantry USCT Regiment in uniform with sword. Library of Congress

Once Black men were allowed to officially enlist in the U.S. military, many freedmen in the Sea Islands chose to fight rather than harvest cotton. By war’s end, around 200,000 Black servicemen would serve with the U.S. Army and Navy, representing 10% of the total U.S. forces. Three-fifths of the Black soldiers were freedmen like the Brown brothers. They knew the territory and fought tenaciously, understanding that their lives, and the lives of their loved ones, hung in the balance.

Cooley, Sam A, photographer. Colored Guard Mounting. Beaufort, South Carolina. 1860. Photograph. Low Country Digital Library

Following his heroic seizure of The Planter, Robert Smalls moved back to Beaufort to buy the house of his former enslaver at a tax auction in 1864. His story became famous in the Sea Islands and, indeed, throughout the Union, and inspired many freedpeople to enlist in the U.S. Army’s first Black regiments from the region - the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Volunteers. These two regiments served in the Sea Islands for the rest of the war, along with the 54th Massachusetts., composed of free Black men from the North. The latter regiment led a courageous raid by U.S. forces at the Battle of Fort Wagner. The 1st and 2nd South Carolina were eventually absorbed into the U.S. Army and conducted numerous raids inland from the Sea Islands, from Darien, Georgia to Jacksonville, Florida.

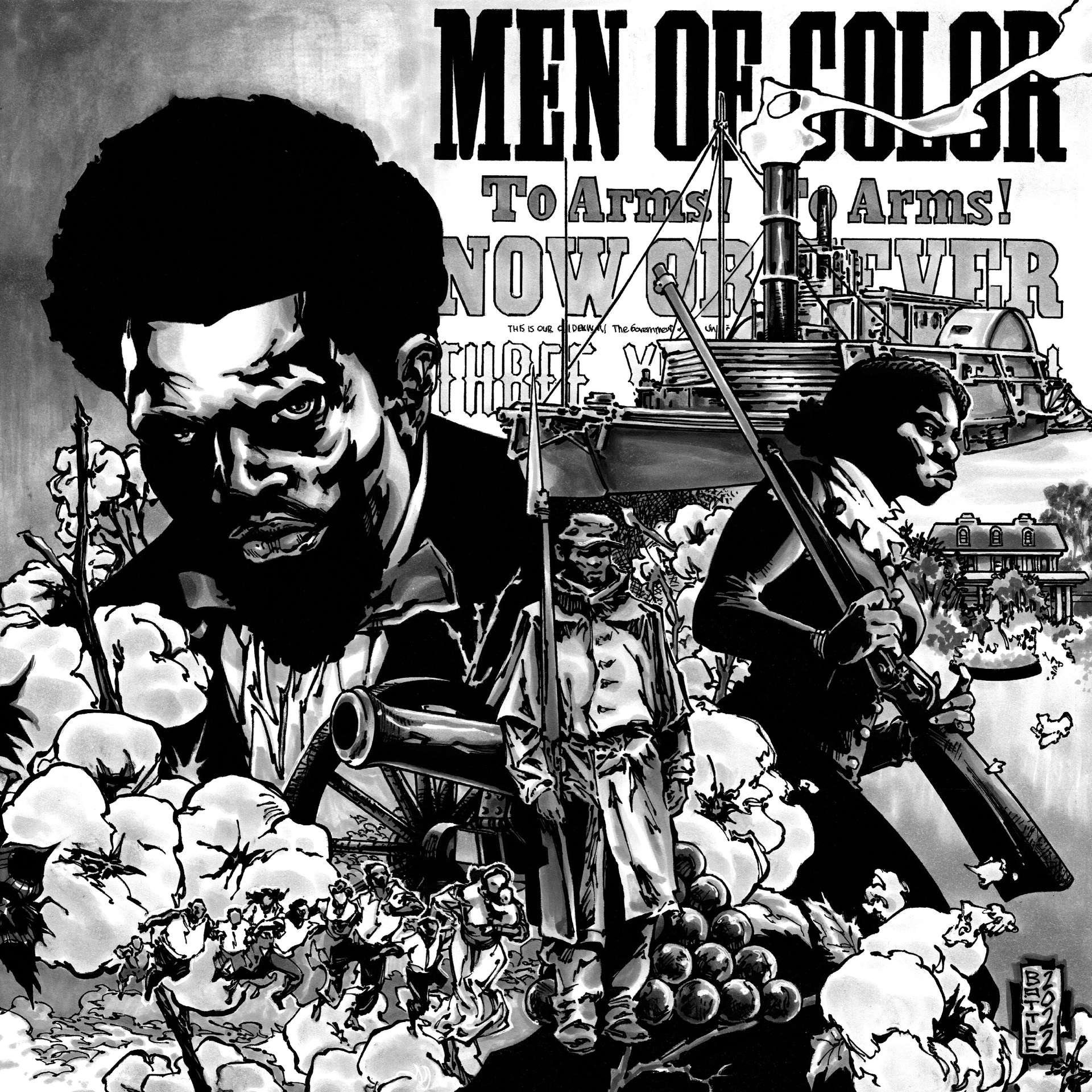

Harriet Tubman

Famous Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman also assisted the U.S. military in the Sea Islands. She volunteered and was accepted to serve the U.S. military effort in 1861 by Major General Benjamin Butler at Fort Monroe in Virginia. Later, she travelled to the Sea Islands region at the request of Massachusetts Governor John Andrew. There she treated Black soldiers and civilians at hospitals in Beaufort, such as the Contraband Hospital, which stills stands today.

Powelson, Benjamin F, photographer. Portrait of Harriet Tubman / Powelson, photographer, 77 Genesee St., Auburn, New York. Library of Congress

Lincoln, Abraham. Emancipation Proclamation, Folded Broadside. Library of Congress

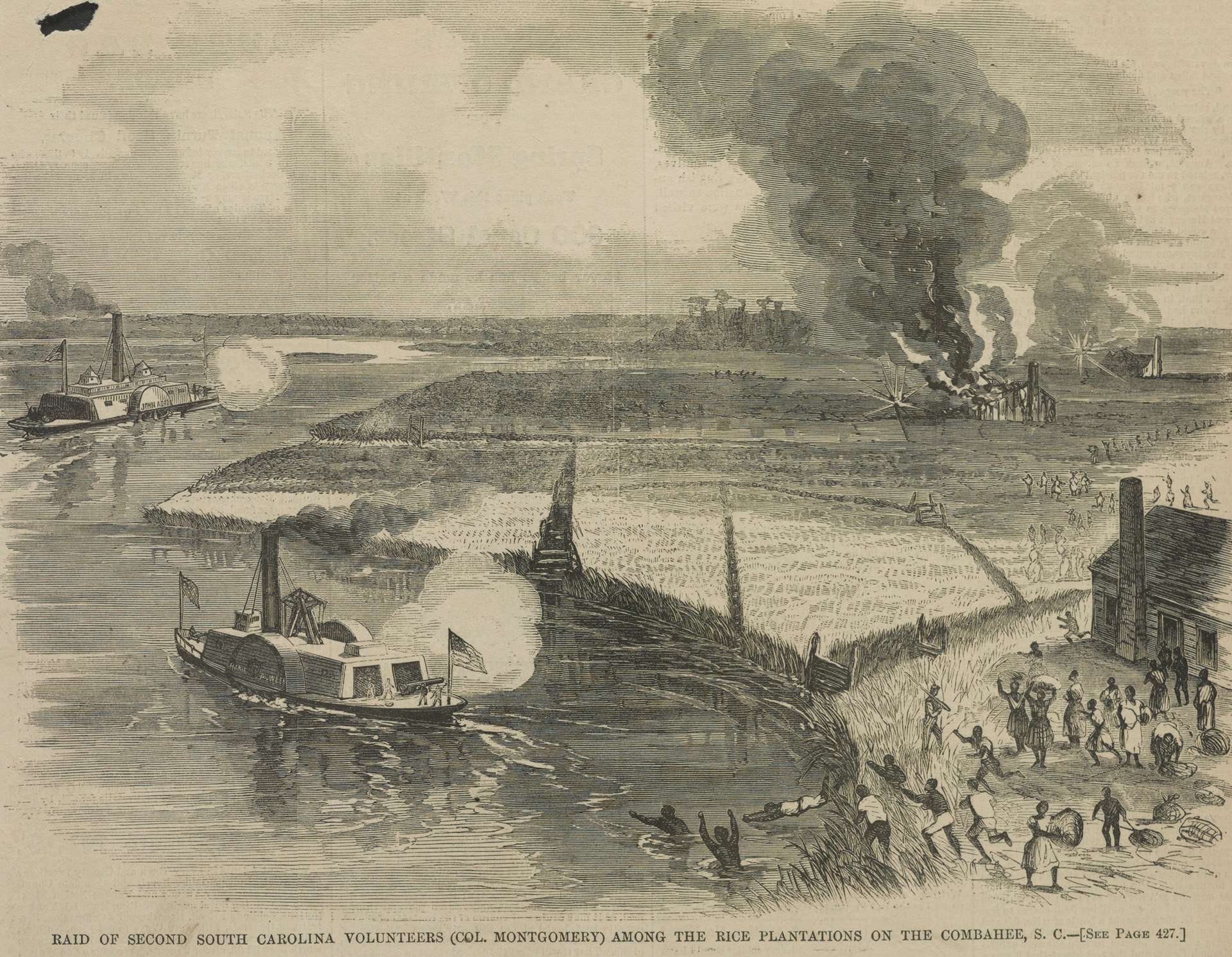

After Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, Tubman began working with Generals David Hunter and Rufus Saxton to find and rescue slaves trapped in nearby areas under Confederate control. From her base at Port Royal, she tapped into a long-established "grapevine" among the area's freedpeople to gather intelligence. On the night of June 2, 1863, Tubman helped lead a mission up the Combahee River with 150 Black soldiers to attack plantations by surprise and liberate as many enslaved people as possible. The raid freed over 700 men, women, and children.

Mcpherson & Oliver, photographer. 2nd South Carolina Infantry Regiment raid on rice plantation, Combahee, South Carolina, and escaped slave named Gordon. Library of Congress

App Stop

Learn more about the Combahee River raid at Stops 9 and 10 of the Free & Equal mobile app.

To download the mobile app visit freeandequalproject.com

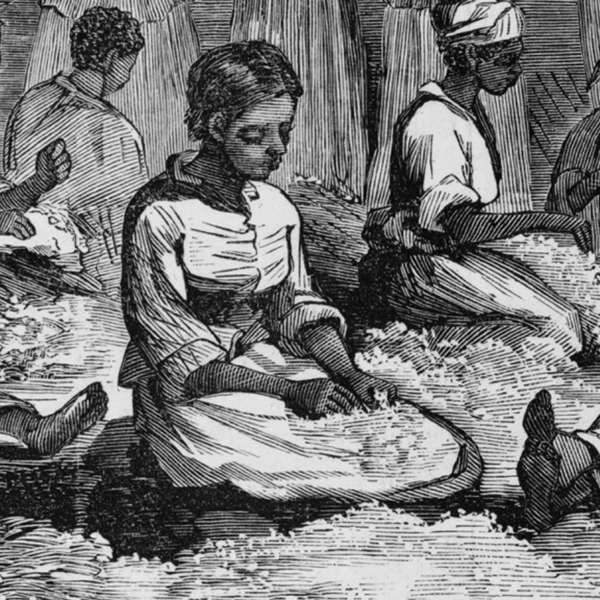

Harvesting Cotton for the War Effort

Government and business leaders wanted to restore cotton production to supply the U.S. war effort. They needed freedpeople to provide the knowledge and labor to do so. Some freedpeople were willing, as long as they could enjoy reasonable wages and better working conditions. They knew their labors would support the U.S. winning the war. They also understood that powerful people might see their efforts as free laborers as proof that they deserved the same rights and privileges that white people enjoyed. That recognition could lead to valuable opportunities and resources, especially land of their own and the chance to receive an education.

Harper's Weekly. Scenes on a cotton plantation. Library Company of Philadelphia

Hubbard & Mix, photographer. Thorpe with Negros working cotton, St. Helena Is. i.e. Island, S.C. Library of Congress

Treasury Secretary Chase chose a Republican lawyer named Edward Pierce to go to Port Royal and oversee the experiment. His mission was to help freedpeople transition out of slavery, while also persuading them to continue working the fields for wages. Establishing schools and providing basic education played a key role in the process. By the time the Port Royal experiment had run its course, Pierce’s superintendents had operated over 100 schools for emancipated children and adults in the Sea Islands.

O'Sullivan, Timothy H, photographer. Port Royal Island, S.C. African Americans preparing cotton for the gin on Smith's plantation. Library of Congress

An Education for All

Many Abolitionists, missionaries, and education reformers from Philadelphia, Boston, and New York watched the war closely. When they learned about the unusual situation at Port Royal and in the Sea Islands, they saw a great opportunity. Dozens of men and women traveled to the area to work with the nation’s first freedpeople. Many came to supervise freedpeople as wage laborers harvesting cotton. Some ran refugee camps. Perhaps most successful were the educators who worked with freedpeople to set up independent schools.

Cooley, Sam A, photographer. School marms and African American children. Library of Congress

Hubbard & Mix, photographer. School Farm, St. Helena Island. Library of Congress

The education, however, went both ways. Most of the Northerners who arrived in the spring of 1862 to supervise the plantations knew almost nothing about cotton cultivation. Freedpeople had to teach many of them how to grow and harvest the crop or the whole operation would have failed.

Cooley, Sam A, photographer. Freedmen's school, Edisto Island, S.C. / Samuel A. Cooley, photographer, Savannah, Ga., Hilton Head, S.C. Library of Congress

While many did not have much choice about whether they worked the cotton crop, local freedpeople leveraged their knowledge as a bargaining chip to negotiate labor contracts. They were able to redefine when and how they would do their work. They would no longer toil every day from sunrise to sundown in gangs under overseers. Instead, they insisted on working a suitable portion of the land with their families. They would now receive wages or a share of the profits for their contribution to the cotton crop. Freedwomen often chose to stay at home with their youngest children rather than work the fields. They now had that choice, something they did not experience under slavery.

Next Chapter

Family & Spirituality

Freedpeople of the Sea Islands forged a new life for themselves with equality as a central principle.