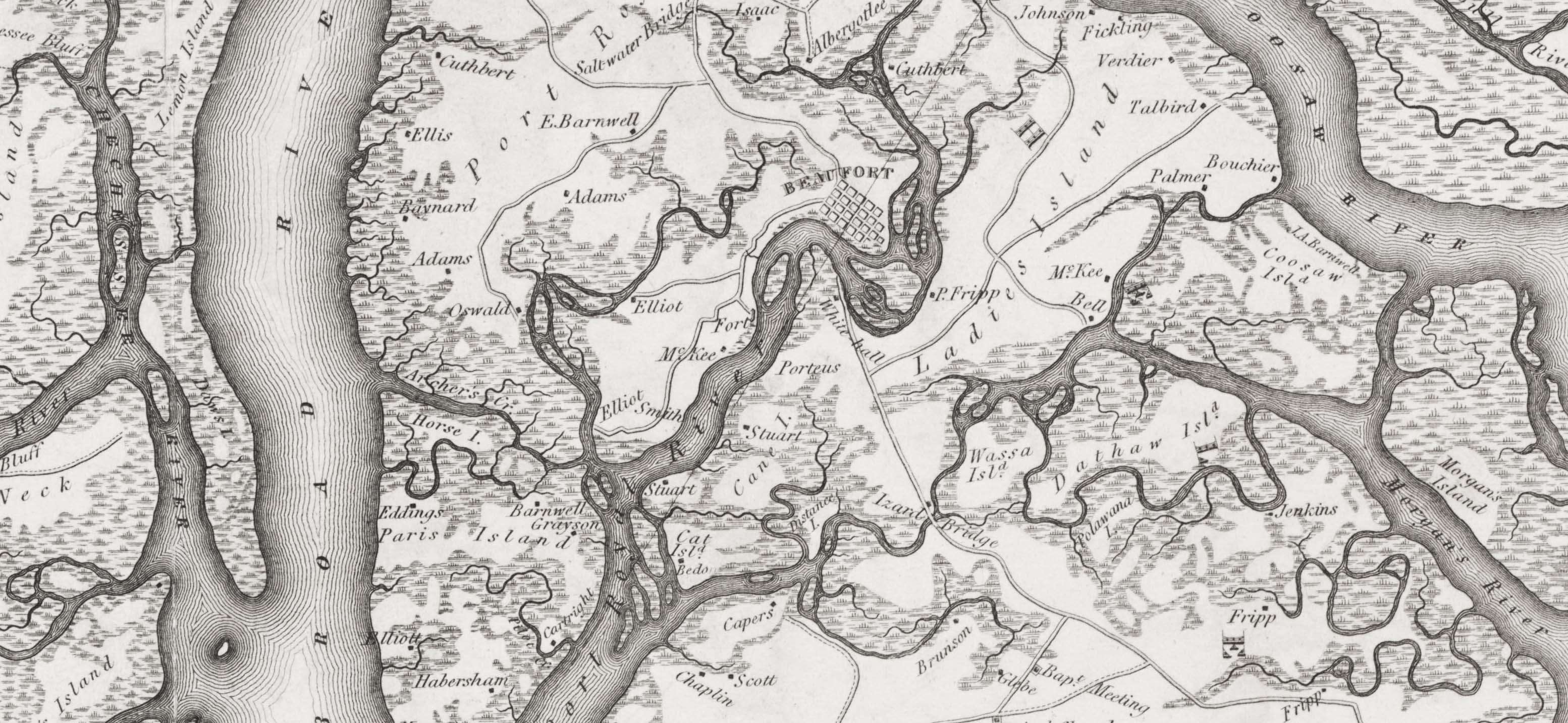

Education & Politics

Education & Politics

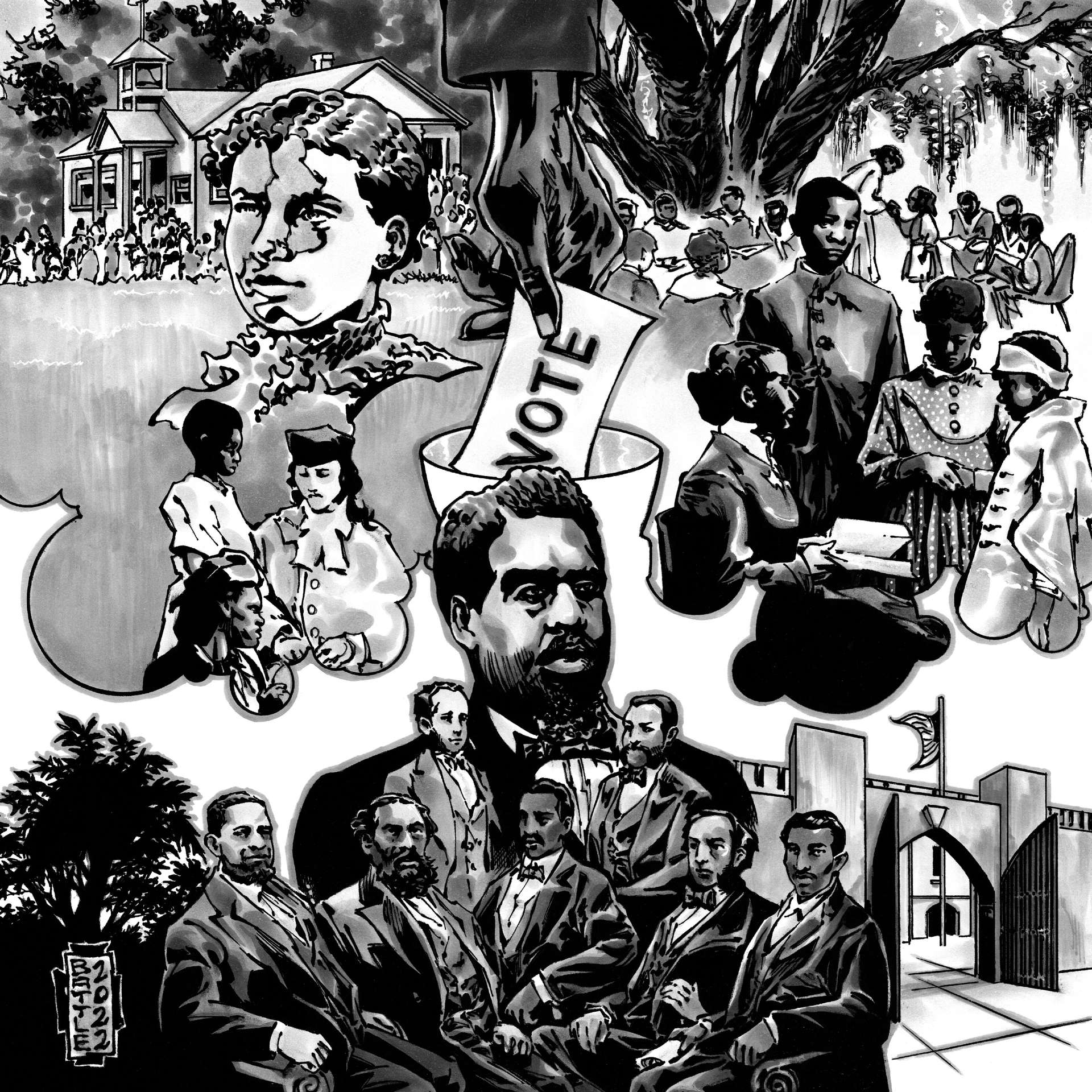

Liberty in the Sea Islands was built on a foundation of education and fulfilled through civic and political engagement.

Educators like Charlotte Forten and Laura Towne helped lead the initiative to educate freedpeople in the Sea Islands, while African American politicians like Robert Smalls exercised political power within new biracial state governments.

Freedom to Learn

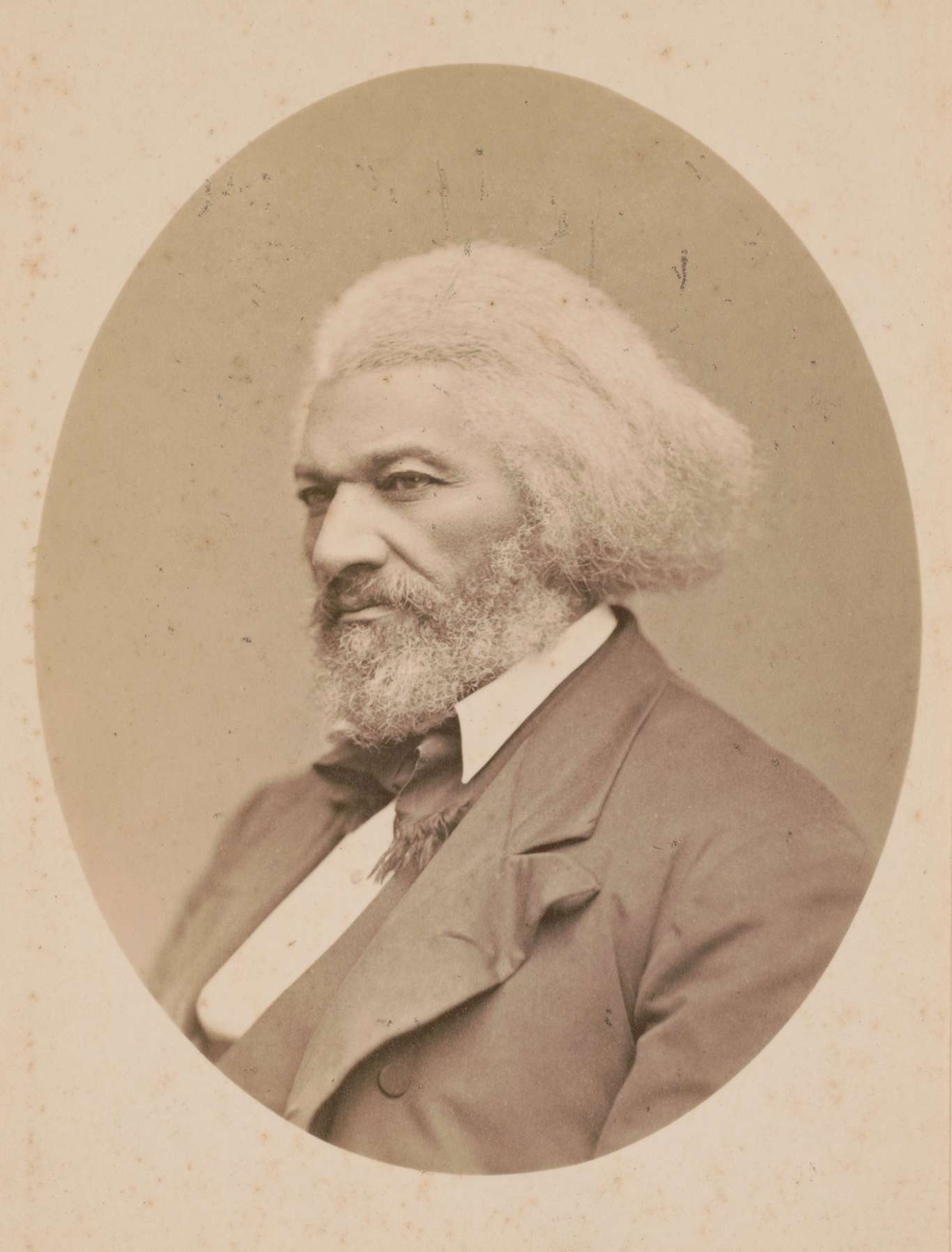

Before the Civil War, most slave states had made it a crime for enslaved people to learn to read and write. Nevertheless, many yearned for an education. A small but significant number of enslaved people did learn how to read and write. The most famous example was Frederick Douglass, who learned to read before escaping from slavery in Maryland in 1838. He became one of the most important orators and writers of his time, and one of the greatest advocates of multiracial democracy in the United States.

Conly, C. F, and G. K Warren, photographer. Frederick Douglass. [Between 1884 and 1890, from negative taken in 1876]. Photograph. Library of Congress

Hubbard & Mix, photographer. Group of scholars on St. Helena Is., SC, No. 1. 1863. Photograph. Library of Congress

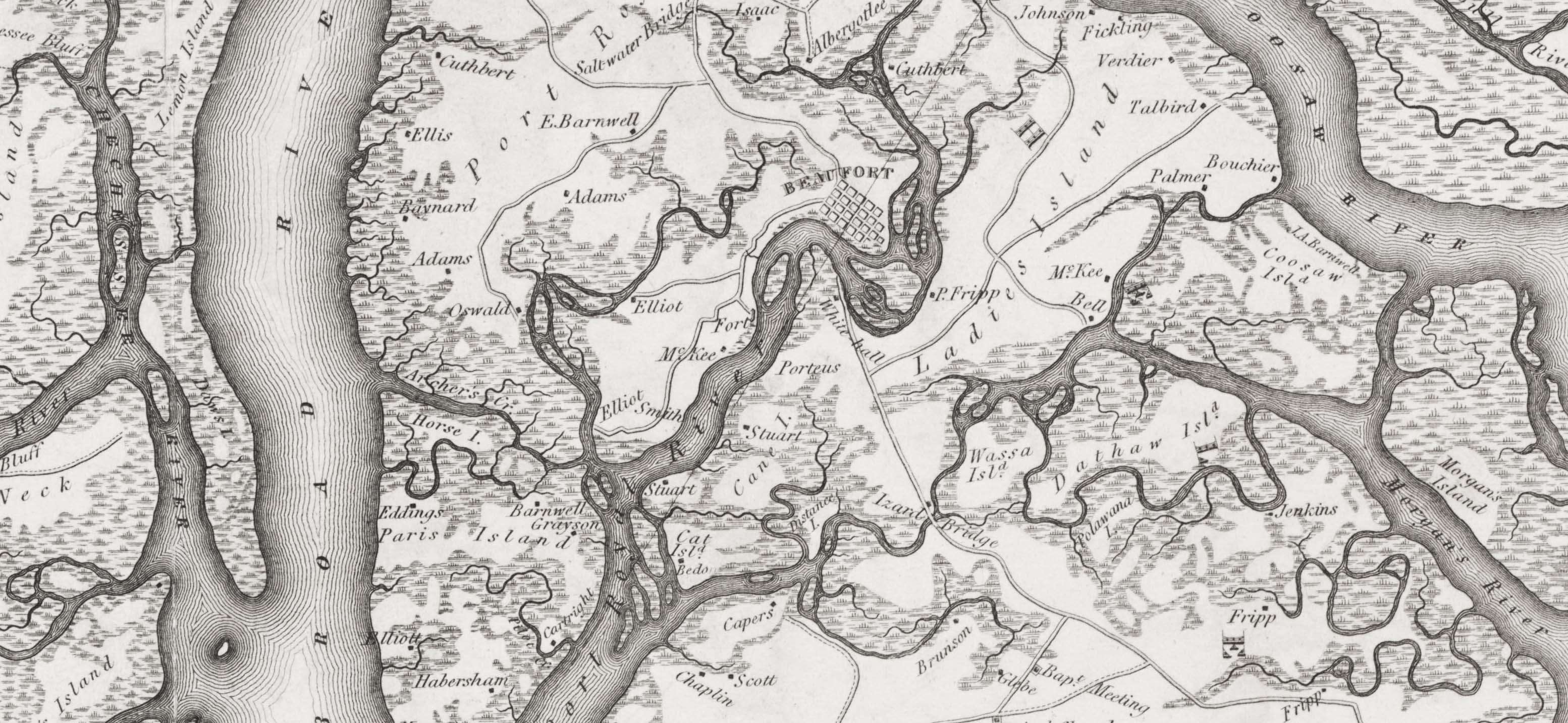

Once emancipated, freedpeople knew that education would be necessary to build new lives, so they sought opportunities to obtain it. When white and Black teachers from Boston, New York, and Philadelphia arrived in the Sea Islands in the spring of 1862 to found schools, they met a community eager for education.

The importance of learning to read was reflected in the music of the day, with songs like Read ‘em, John:

John wrote a letter and he laid it on the table

No one can read ‘em like ol’ John

Read ‘em, let me go

App Stop

In the Free & Equal mobile app, you can hear “Read ‘Em John” performed by Grammy-award-winning Gullah singers Ranky Tank. Check out stop 3 of the mobile app.

To download the mobile app visit freeandequalproject.com

American Freedman's Union Commission. Pennsylvania Branch. Philadelphia, 1865 or after. Library of Congress

Laura Towne

Many of the visiting educators held strong abolitionist beliefs, none more so than Philadelphia teacher Laura Towne. While others may have focused on the strategic value of educating freedpeople to support the war effort, she saw the Port Royal Experiment as a thoroughly anti-slavery endeavor.

Towne, Laura Matilda. Author. Letters and diary of Laura M. Towne. 1912. Cornell University Library. Internet Archive

In her diary she wrote about her desire that all Northern educators boldly express their abolitionist beliefs:

I think a rather too cautious spirit prevails—anti-slavery is to be kept in the background for fear of exciting the animosity of the army…. I wish they would all say out loud quietly, respectfully, firmly, ‘We have come to do anti-slavery work, and we think it noble work, and we mean to do it earnestly.’

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, New York Public Library Digital Collections

Towne arrived in the Sea Islands in April of 1862. Together with Ellen Murray, she founded what would later become the Penn School in an old plantation house on St. Helena Island. Though they admitted students of all ages, the teachers designed their classes primarily for children, knowing that they would go home at night and teach the lessons they had learned to their entire families.

Hubbard & Mix, photographer. Miss Laura Town's i.e. Towne's school, St. Helena Island, South Carolina. South Carolina United States Saint Helena Island, 1863. Photograph. Library of Congress

Unlike most of the Northerners who traveled to Port Royal, Towne stayed for the next forty years, running the Penn School until her death in 1901. Today the school is one of the four sites that form the Reconstruction Era National Historic Park.

App Stop

In the Free & Equal mobile app, you hunt down Laura Towne’s somewhat hidden grave in stop 13 and get a chance to see the original school she built at Penn Center via augmented reality. It’s stunning and touching. Download the app now to see that school and her grave on site or from the comfort of your own home.

To download the mobile app visit freeandequalproject.com

Charlotte Forten

Born in Philadelphia to a wealthy Black family, educator Charlotte Forten also traveled to the Sea Islands in 1862 with the goal of educating and elevating freedpeople. She joined Laura Towne at the Penn School and was a leader in the community.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. "Lottie Grimke." New York Public Library Digital Collections

In 1864, the Atlantic Monthly published her article “Life in the Sea Islands.” She described the optimism of her Sea Islands students, writing:

The long, dark night of the Past, with all its sorrows and its fears, was forgotten; and for the Future—the eyes of these freed children see no clouds in it. It is full of sunlight, they think, and they trust in it, perfectly. This is our home and we have made these lands what they are. Were the only true and loyal people that were found in possession of These lands… Are not our rights as a free people and good citizens of these United States to be considered before the rights of those who We found in rebellion against this good and just government?

Voting and Civic Life

Freedpeople in the Sea Islands understood that without political representation, it would be impossible for them to protect and sustain their freedom. They argued for the right to vote and hold elected office.

Electioneering at the South / sketched by W.L. Sheppard. 1868. Illustration. Library of Congress

A Sea Islands refugee settlement called Mitchelville was one of the earliest examples of African American political and civic participation. Major General Ormsby Mitchel decided in late 1862 to work with freedpeople to build housing and develop civic institutions for those gathered on Hilton Head Island. Under military supervision, freedmen served on the city council and made decisions about local education and policies. At its height, the town reached an area of 200 acres and between 1,500 and 3,000 residents.

Port Royal Island / From sketches by our special artist. Mitchellville Port Royal, 1863. [New York: Frank Leslie, Feb. 7] Photograph. Library of Congress

In 1865, delegates from across the state traveled to Charleston for a statewide political convention of African Americans. The contingents from Charleston and Beaufort were especially large. Convention participants spoke eloquently about their visions of freedom. They emphasized the need for education, the ability to do business without interference, and the rights to vote and hold office. The convention culminated in an appeal to the state of South Carolina to repeal racist laws that hindered Black people from making progress. They demanded, for one, “the inestimable right of voting for those who rule over in the land of our birth.”

Davis, Theodore R., Artist. The National Colored Convention in session at Washington, D.C. / sketched by Theo. R. Davis. Washington D.C, 1869. Photograph. Library of Congress

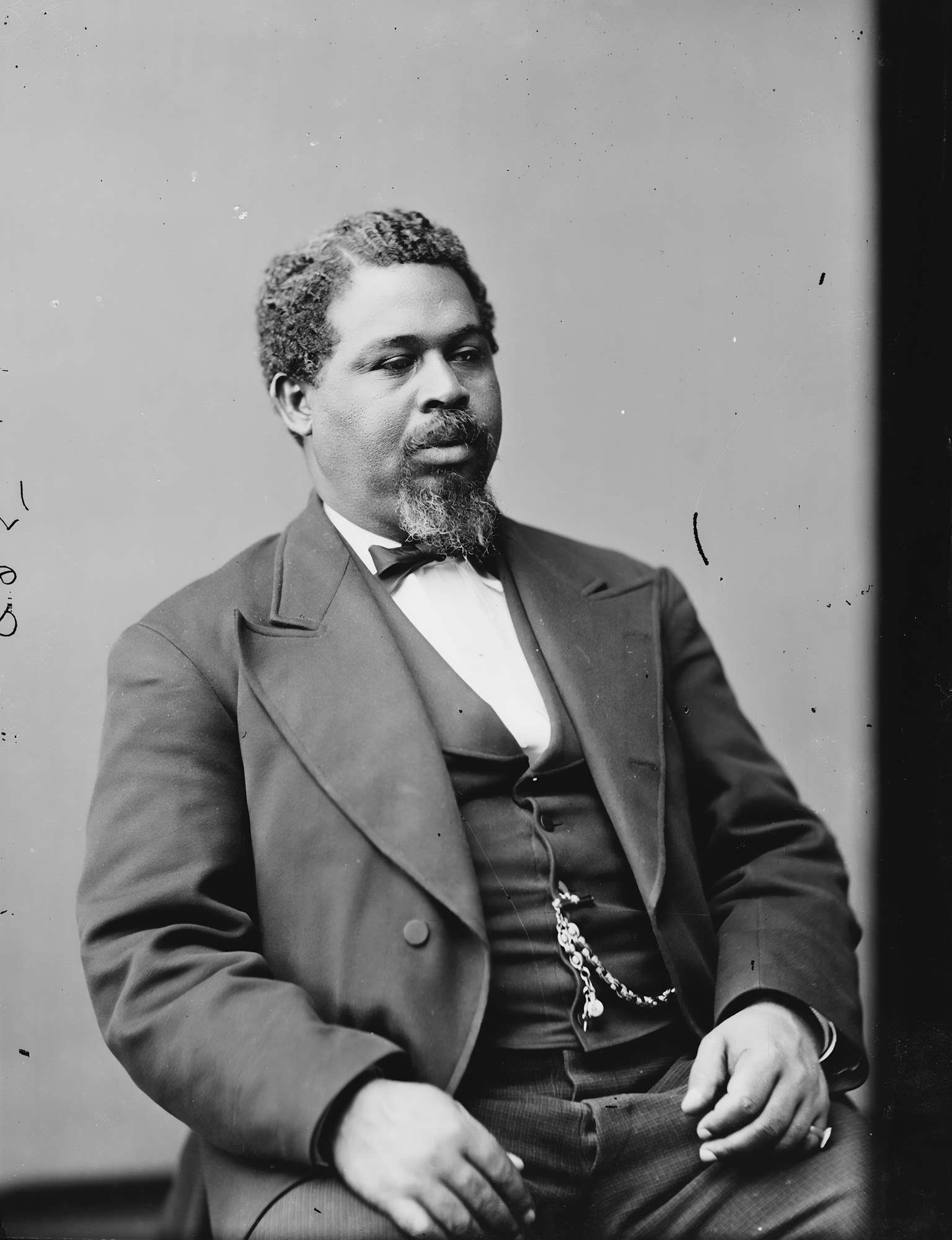

During postwar Reconstruction, Black people gained considerable political power in states where they were a substantial proportion of the population. These included Mississippi, Louisiana, and South Carolina, where Black people made up about 60% of the population. Enfranchised through federal policy, more than 80,000 Black men in South Carolina registered to vote for delegates to the new state constitutional convention that met in Charleston in 1868. The new biracial governments had many achievements, including establishing the South’s first public school systems, and passing laws to guarantee equal treatment regardless of race in transportation and public accommodations.

Extract from the reconstructed Constitution of the state of Louisiana, with portraits of the distinguished members of the Convention & Assembly, A.D. Louisiana, 1868. Photograph. Library of Congress

Throughout the South, white residents tried to prevent freedpeople from owning weapons to protect themselves and their communities. During Reconstruction, the state authorized the formation of militia units largely composed of Black men. The militia formed by freedmen in Beaufort was one example. The Arsenal in Beaufort had been a prison to enslaved people and a shelter for whites in the event of a slave uprising. During Reconstruction, the local Black militia took over the Arsenal to store their weapons.

App Stop

In the Free & Equal mobile app, you can relive this unique resistance to Jim Crow in Beaufort’s arsenal. An augmented reality animation on top of an old photograph of the Arsenal shows how this resistance went down. Check it out by downloading the app and going to chapter 10.

To download the mobile app visit freeandequalproject.com

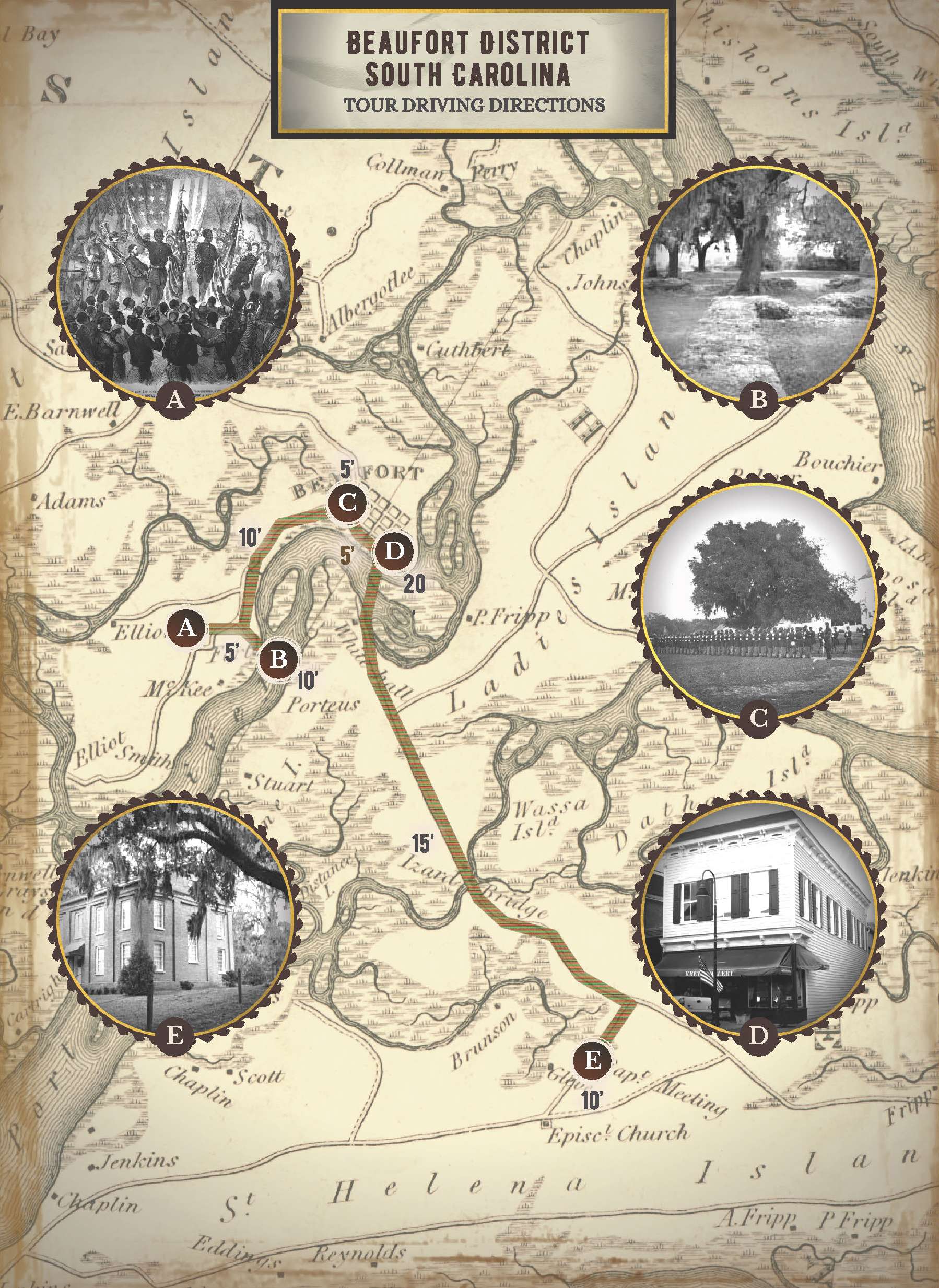

Robert Smalls, the Politician

Robert Smalls exemplified the African American political power that persisted in South Carolina well into the 1870s, and in the Sea Islands far longer. In 1867, Congress mandated the establishment of new state governments in most of the South, with African Americans voting and holding office. Smalls won his first office in 1868 when he ran for the South Carolina State House of Representatives.

Robert Smalls, S.C. M.C. Born in Beaufort, SC, April. , None. [Between 1870 and 1880] Photograph. Library of Congress

In Beaufort, where Black people outnumbered white people seven-to-one, Smalls was repeatedly re-elected to office. He won a seat in the U.S. Congress in 1874 and served five terms. Despite the Democratic majority in the U.S. House of Representatives, he won several infrastructure improvements for the Sea Islands.

The first colored senator and representatives - in the 41st and 42nd Congress of the United States, New York : Published by Currier & Ives, 1872. Library of Congress

Many whites feared and rebelled against their loss of control over Southern labor and land as it threatened the system of white supremacy. They resented Black people in positions of power and took extreme measures to resist federally supported Reconstruction. Just as they had during the war, white South Carolinians used violence against African American men trying to vote or pursue elected office in 1876. Still, by the end of Reconstruction in 1877, approximately 2,000 African American men had been elected or appointed to public office across the former Confederacy. Seventeen of them served in U.S. Congress, and 600 served in state legislatures.

Next Chapter

Labor & Land

Nowhere else in the South did freedpeople have better opportunities to own land and earn a fair wage.